His first film as a writer and director, Shina, remained on the Netflix Top 10 chart for weeks after its release on June 14, 2024, a surreal experience for him considering where he started from.

The filmmaker believes a good story must be marketable, but emphasises that the cost of filmmaking is incredibly daunting, making it difficult to create art for art’s sake.

In an exclusive interview with Pulse Nigeria, Adesokun discusses his journey as a filmmaker, and the future of his career.

You seem to have transitioned from literary writing to filmmaking. How has the journey been?

I’ve always been interested in filmmaking. As a kid, I would watch the credits after a film and imagine how amazing it would be to be part of the team that created it. While writing poetry and making films may seem worlds apart, I’ve found a connection between the two in storytelling. Both mediums aim to tell a story, and that made the transition feel natural for me.

As a writer and director, what are the things you look out for before deciding to work on any film?

The story is the heart and soul of any project. Everything begins with the story — what message it conveys and how it resonates. It all starts there.

What was your creative process from script to screen for Shina?

As a writer, I consumed a lot of resources. Read so many scripts of films I thoroughly enjoyed. Aaron Sorkin is a screenwriter I admire a lot. Some of his works include The Social Network (one of the best films I’ve ever watched), A Few Good Men, and The West Wing. Understanding his approach to film was a major step in my process.

After completing the script, it was then reviewed and I got feedback from other writers and producers. These discussions also led to potential casting and things like that. In preparing to direct I also consumed content from filmmakers like Jordan Peele and Quentin Tarantino. Their different approaches to filmmaking inspired me.

Shina was on the Netflix Top 10 chart weeks after its release, how did that feel for you and your team? What did that mean to you personally?

It was surreal. I didn’t expect it to be on Netflix for 49 days, seven weeks! In addition, it’s the second most-watched film on Netflix in 2024 in Nigeria. It means a lot to me and the team. It surpassed our expectations.

How would you describe your working experience with the cast and crew?

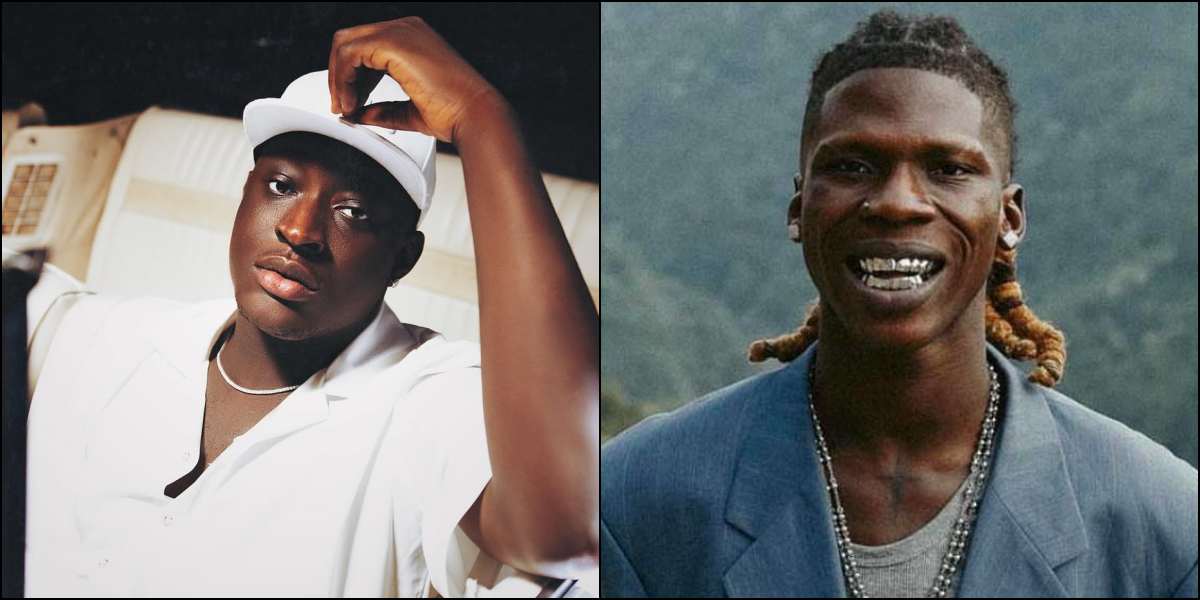

Fantastic! I couldn’t have asked for a better team for my debut. We forged relationships and friendships that will last a lifetime. This project was full of firsts — my first time writing and directing, Carmen Lilian’s first time directing, and Timini’s first time as an executive producer.

Nollywood has changed over the years. Some films today focus more on profitability than art. How do you balance the artistic and commercial aspects of filmmaking?

It’s challenging. As a creative, it’s easy to become entirely focused on your art, but creating a film requires a lot of resources. The good news is that a strong story or project tends to attract interest and investment. It becomes easier to get people on board. For me, a good story strikes the right balance — creatives enjoy making something remarkable, and for investors, there’s almost a guarantee of return on investment. However, no matter how good a story is, it must be marketable. That simply means it must have the potential to connect with its audience in a relatable way.

Would you like to share some milestones you’re particularly proud of?

I’m thrilled that the body of work I’ve put out so far has been well received. My book, The Taxi Driver and Other Poems debuted at number 14 in African Poetry worldwide on Amazon. As for Shina, I mentioned the milestones earlier. I’m just grateful to see the goals I set seven or eight years ago are coming to life.

Challenges they say are a part of life. What are some of the challenges you’ve faced and probably still facing as a filmmaker?

A major challenge is the cost of making a film. If I were to make Shina today, it would cost double or even triple what it did originally. The cost of filmmaking continues to rise at an alarming rate, which is daunting. This ties back to my earlier point — it’s become too expensive to create art for art’s sake. Today, it has to be profitable.

What significant changes have you observed in Nollywood over the past decade?

More and more people are devoting themselves to filmmaking, and every year the bar seems to rise. There’s a growing competition to create the next best film, with filmmakers constantly pushing the limits. As a result, Nollywood is only getting better.

What would you say are the notable strengths and weaknesses in the industry?

I believe the industry’s strength lies in its people — writers, directors, actors, producers, crew members, journalists — the entire ecosystem. As for weaknesses, I think there’s room for more collaborations. By working together, we can firmly establish Nollywood as one of the world’s top film industries. We have the stories, and we have the talent; we just need to collaborate more.

Who are your biggest influences in the film industry, and how have they shaped the kind of work you do?

Definitely Kayode Kasum. He’s exceptional at what he does. His attention to detail, passion for storytelling, and relentless drive to outdo his previous work are truly inspiring. I’m also inspired by the works of Kemi Adetiba and BB Sasore.

How do you balance your career as a filmmaker and your personal life?

I believe they fuel each other — success in one area energises the other. I also have a great support system. Being a stickler for time management helps me make the most of each day, though I often wish there were more than 24 hours.

What advice do you have for aspiring filmmakers looking to make their mark in the film industry?

Learn how to write for film and television. It’s a skill that will make you a better storyteller and benefit you throughout your career. And most importantly, just go for it — do everything you can to make your first film.