The city was a drumbeat, pulsing under neon skies and the restless hum of traffic. Lagos, in the early 1980s, carried its ambitions like smoke — visible, yet elusive, slipping between palms and over rooftops. Concrete and humidity intertwined, creating an atmosphere heavy with possibility, as if the very air waited for something to ignite.

Inside the National Theatre, the walls themselves seemed to lean closer, listening. The seats were empty but expectant, the polished floors reflecting flickers of fluorescent light like distant stars waiting to be called into being. Somewhere, a projector waited silently, a mechanical heartbeat poised to give life to dreams that had grown restless in the shadows.

Outside, the city murmured rumors, whispers of change, tension, and unseen forces shifting like clouds before a storm. Ambition and anxiety danced together in the streets, in the offices of filmmakers, in the studios where reels lay coiled like sleeping serpents. The night seemed to hold its breath, as though knowing that the ordinary could become extraordinary — or vanish entirely — in an instant.

This is a story of waiting. Of hopes poised at the edge of light and shadow. Of dreams that hovered in the air, ready to bloom, yet threatened by forces beyond their control. And as Lagos exhaled softly into the humid night, those suspended possibilities were about to meet history — in a silence that spoke louder than any applause.

Reels, Ambition, and the Nigerian Film Corporation

By the early 1980s, Nigerian cinema was at a crossroads. The civil war had ended barely a decade earlier, and filmmakers were trying to establish an industry capable of both entertaining and educating. Directors like Hubert Ogunde and Ade Love had begun translating Yoruba traveling theatre into film, while younger voices — Ola Balogun, Eddie Ugbomah, and Jab Adu — were experimenting with narratives that spoke to a postcolonial identity.

The Nigerian Film Corporation (NFC), established in 1979, was the government’s primary instrument for cultivating cinema as a cultural and diplomatic tool. Under Shagari’s administration, the NFC sought to standardize production, offer grants, and support film screenings nationwide. It aimed to give filmmakers access to 35mm equipment, training, and distribution channels — a promise that seemed revolutionary to a generation used to improvisation and stage tours.

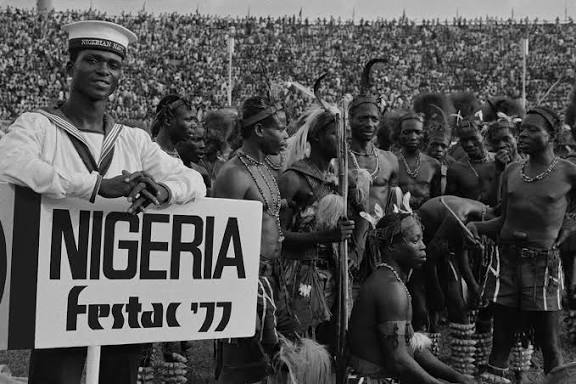

Throughout 1983, NFC staff worked tirelessly to coordinate screenings, workshops, and exhibitions. Plans were made to bring together filmmakers from Lagos, Ibadan, and Enugu, as well as international visitors, to showcase Nigerian talent. Scripts were reviewed, reels cataloged, and publicity arranged through the Nigerian Television Authority (NTA) and local newspapers. The halls of the National Theatre, rebuilt and polished for FESTAC ’77, were envisioned as the stage for this cultural assertion.

But the ambition was fragile. Economic decline, rising corruption scandals, and political unrest cast shadows over even the most meticulous planning. Filmmakers worked against a backdrop of uncertainty, aware that the state’s support could vanish overnight. Still, they pressed on — editing, rehearsing, and shipping reels — carrying the quiet hope that Nigerian cinema could finally claim its voice on a national stage.

A City on Edge

Lagos in December 1983 was a city of contrasts. Shiny new cars mingled with rickety buses; street vendors hawked roasted corn beneath neon signs; the hum of generators competed with distant radio broadcasts. People moved quickly, eyes alert, sensing that the air itself carried tension. Rumors of a military takeover had circulated for weeks, whispered in offices, bars, and taxi cabs.

Inside the National Theatre, that tension was amplified. Projectionists tested reels for defects, ushers rehearsed seating assignments, and organizers double-checked schedules. Every flicker of a projector bulb, every squeak of a folding chair seemed amplified, feeding the collective anxiety of those gathered. The filmmakers, accustomed to improvisation and resilience, sensed that fate might intervene in ways no editing room could control.

By late evening, the atmosphere thickened. Conversations slowed, laughter became cautious, and the hum of the air conditioning was the only constant. Staff moved like shadows, aware that they were holding a fragile ecosystem of culture together, moment by moment, against the pressures of a city brimming with political uncertainty.

When the first reports of troop movements reached the theatre, the audience initially dismissed them. Lagos had experienced unrest before. But the tension persisted, a silent drumbeat that foreshadowed the events to come. That night, the city itself seemed to be holding its breath.

The Coup That Silenced Cinema

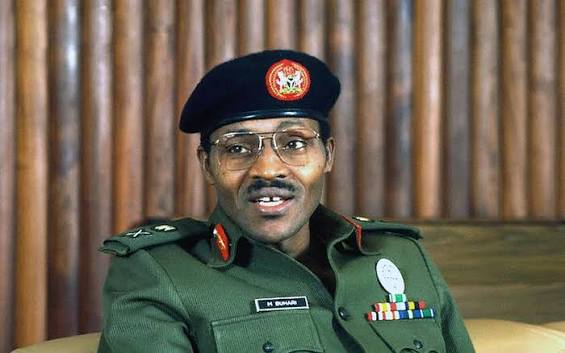

The coup of December 31, 1983, led by Major-General Muhammadu Buhari, swept through Lagos with military precision. Government offices, radio stations, and strategic locations were seized before dawn. The new administration justified its action on the grounds of corruption and inefficiency, but its arrival had immediate and devastating consequences for culture.

The NFC’s operations were abruptly disrupted. Film grants were frozen, programs suspended, and many projects canceled or indefinitely postponed. Equipment and reels that had been prepared for screenings were stored, forgotten, or left unclaimed. Filmmakers faced uncertainty; some were questioned by military authorities, while others quietly relocated or retreated into less politically sensitive forms of media, such as television or home video.

The National Theatre — poised to host Nigeria’s emerging cinematic ambitions — fell silent. Its projectors, meticulously calibrated for premieres, were left idle. Screenings planned for that week, months in preparation, never happened. The city’s cultural heartbeat, for a brief moment, faltered under the weight of political upheaval.

For many filmmakers, the coup was not just a political event; it was a personal rupture. Dreams, careers, and ambitions were suspended in a way that could not easily be resumed. The machinery of storytelling had been paused — and it would take years for it to restart in full.

The Frozen Dreams of Filmmakers

In the immediate aftermath of December 31, 1983, the Nigerian Film Corporation’s offices were transformed almost overnight from bustling centers of creativity into places of hushed uncertainty. Desks once stacked with scripts and film reels now held empty files and canceled correspondence. Editors, producers, and projectionists who had spent months preparing screenings were left in limbo, unsure if their work would ever see the light of day.

Eddie Ugbomah, whose films had critiqued social and political issues, found his projects under scrutiny. Reels that had been scheduled for public viewing were locked away “pending review,” a bureaucratic euphemism for permanent suspension. Ola Balogun, who had been developing a new feature exploring economic disparity, paused production entirely. Younger filmmakers, many just emerging from apprenticeships in theatre or television, found themselves navigating a landscape where ambition had to be measured against survival.

The silence extended beyond offices. The National Theatre, once alive with rehearsals, discussions, and the hum of projectors, became eerily still. Even routine screenings for diplomats, journalists, or visiting artists were canceled. The grandeur of FESTAC ’77, still a memory in the hall’s painted murals, seemed to mock the emptiness of the present. It was not violence that killed the cultural momentum — it was the subtle, pervasive control of a regime that saw storytelling as a potential threat.

Psychologically, the impact was profound. Many filmmakers later recalled a sense of paralysis — a quiet censorship that did not require orders or decrees. The message was clear: art could flourish, but only within boundaries approved by power. Dreams that had once seemed national in scope were reduced to whispers in offices, private studios, and the occasional informal screening at homes or community centers.

Cultural Aftershocks Across Nigeria

The coup did more than freeze individual projects; it reshaped the very perception of Nigerian cinema. Cultural initiatives under Shagari had promoted film as a tool for diplomacy, education, and national pride. With military oversight, funding was reallocated toward “priority information tasks,” propaganda, and state-controlled television content. Films that critiqued society were seen as potential acts of dissent rather than national assets.

The ripple effect was felt beyond Lagos. Across Nigeria, budding filmmakers struggled to secure equipment, funding, or official approval. Universities and theatre troupes, once vibrant incubators of talent, faced restrictions or audits. Artists were forced to improvise, shifting to mediums less likely to attract suspicion — radio dramas, home video, and community theatre. Even international collaborations slowed, as foreign partners became cautious of the political climate.

Historians later observed that this period, though painful, shaped Nigerian cinema in unexpected ways. The abrupt withdrawal of institutional support forced filmmakers to innovate. Where once the NFC had offered structured opportunities, a vacuum now existed — a vacuum that would eventually be filled by independent, entrepreneurial approaches to filmmaking. Necessity, as it often does, became the mother of invention.

In retrospect, the silence imposed by the coup was both destructive and transformative. It killed certain dreams but incubated others. By limiting access to traditional production channels, the regime inadvertently prepared Nigerian filmmakers for the decentralized, agile model that would define Nollywood in the decades to come.

The Lost Reels and Forgotten Archives

For decades, the films, scripts, and reels prepared for screenings in late 1983 remained in storage, some forgotten, others decaying in humid vaults. The Nigerian Film Corporation maintained archives, but without funding or personnel to preserve them, many pieces of celluloid suffered irreversible damage.

In the early 2000s, archivists rediscovered dozens of reels labeled with production titles and tentative screening notes. Among them were works by Eddie Ugbomah, Ola Balogun, and lesser-known filmmakers from Lagos and Ibadan. While many reels had warped, torn, or dissolved entirely, the surviving materials offered historians a glimpse of what might have been — a national cinematic awakening cut short by political upheaval.

The discovery sparked renewed discussions about cultural preservation and the fragility of artistic heritage in politically unstable contexts. Scholars, journalists, and filmmakers began piecing together narratives from newspapers, correspondence, and oral histories. These reconstructions confirmed the ambitions of the early 1980s: Nigeria had been poised for a significant moment in cinema, one that could have fostered critical discourse, African collaboration, and international recognition years before Nollywood emerged.

Even in decay, the reels were a testament to resilience. They reminded the nation that creativity had existed, had been nurtured, and could endure — if only its caretakers remained vigilant.

From Silence to the Birth of Nollywood

By the 1990s, Nigeria’s cinematic landscape had shifted dramatically. Military regimes continued to dominate, but technological innovations created new opportunities. Home-video recorders, VHS, and later affordable digital cameras allowed filmmakers to bypass traditional institutions. Stories once frozen by bureaucracy or fear now reached audiences directly, often in living rooms, community halls, and informal markets.

The pioneers who had seen their ambitions stalled in 1983 became mentors and advisors to this new generation. Equipment, scripts, and editing knowledge were shared quietly, almost clandestinely, enabling grassroots production. Where the National Theatre had once symbolized prestige and state approval, the streets, homes, and markets became the stages of Nigerian storytelling.

This shift democratized cinema. It transformed storytelling from a government-endorsed activity into a people-driven enterprise. The spirit of the 1983 ambitions — of reaching audiences, telling national stories, and asserting Nigerian identity through film — survived, not in formal festivals, but in the resilience and ingenuity of filmmakers.

Nollywood, in essence, became the unofficial heir to the dreams frozen by the coup. Each home-video drama, village epic, or urban thriller carried echoes of a time when a nation almost held its first cinematic festival — a reminder that art can endure even under the shadow of power.

The National Theatre: Monument and Memory

Today, the National Theatre in Iganmu stands as a silent witness to decades of Nigerian cinematic ambition and political turbulence. Its walls, once gleaming after FESTAC ’77, show the weathering of time; its stage, once rehearsed for premieres, remains mostly dark, lit occasionally for state ceremonies, weddings, or temporary cultural events.

The building is both monument and memory, a physical reminder of what might have been in 1983.

Visitors often remark on the Theatre’s imposing presence. Its high dome, murals celebrating African unity, and cavernous halls evoke both awe and melancholy. In quiet corners, archivists and older filmmakers recount stories of early screenings, rehearsals, and workshops — of the era when the National Theatre almost hosted Nigeria’s first major cinematic festival. Those memories linger in the air, a kind of invisible celluloid, a whisper of ambition interrupted.

For filmmakers, the Theatre is more than architecture. It is a symbol of resilience, of potential stifled by politics but never fully erased. Modern directors, curators, and festival organizers still return to its halls, conducting workshops, screenings, and masterclasses, as if to reclaim the space that history once denied them. The echoes of past reels, lost and stored, mingle with the voices of a new generation, creating an intangible bridge between ambition halted and creativity unleashed.

Even government promises of restoration, sometimes delayed or incomplete, carry symbolic weight. Funds are allocated, committees convened, and renovations planned — often late, often bureaucratic. Yet the act of attempting to preserve or reopen the Theatre reinforces a truth understood by every Nigerian filmmaker: the power of storytelling cannot be fully contained, even by military regimes or political instability.

Modern Festivals and Cultural Reclamation

In the 21st century, Nigeria has witnessed a cultural renaissance. Film festivals such as the Africa International Film Festival (AFRIFF), iREP Documentary Festival, and various city-based events have brought international attention to Nigerian cinema. Many of these events deliberately choose historic spaces like the National Theatre to stage screenings, blending past memory with present ambition.

These festivals serve multiple purposes. They offer platforms for filmmakers to showcase narratives exploring politics, social change, identity, and heritage. They act as spaces for mentorship, teaching, and cross-cultural collaboration. And importantly, they reclaim historical spaces — the same halls that in 1983 had waited in silence now hum with discussion, debate, and applause.

The legacy of the 1983 interruption is never far from these events. Organizers often acknowledge the lost opportunities of earlier decades, framing current successes as both continuity and reclamation. Where once ambition was frozen by political upheaval, it now flourishes under the radar of resilience, creativity, and the informal networks of artists determined to tell their stories.

Through this reclamation, the National Theatre transforms from a symbol of failure into a living archive, a reminder that Nigerian cinema, though shaped by interruption, is defined by endurance. Every screening, every audience, every discussion is a quiet defiance of the historical forces that once silenced ambition.

Closing Reflection: Resistance in Celluloid

The 1983 coup did not kill Nigerian cinema; it merely paused a moment of possibility, leaving behind both loss and latent energy. Films that never screened, projects that were frozen, and dreams that were deferred became lessons for a generation of filmmakers: art cannot rely solely on institutional support; it must survive, adapt, and innovate.

When home-video technology emerged in the 1990s, it was not simply a technical advancement — it was the manifestation of resilience. Nollywood’s explosive growth was in many ways a response to absence, a reclaiming of narrative space denied by politics. The stories of Lagos, Ibadan, Enugu, and countless other towns could now reach audiences directly, without waiting for official sanction or festival approval.

The National Theatre, the NFC, and the memories of 1983 continue to teach. They remind contemporary filmmakers that cinema is fragile but enduring, vulnerable but revolutionary. Each reel, each recording, and each screening is part of an ongoing conversation with history — a dialogue between ambition interrupted and creativity realized.

Ultimately, the lesson of that darkened night in December 1983 is this: power can halt government and suspend institutions, but it cannot erase imagination. The aborted festival may never have taken place, but its spirit survives in every Nigerian filmmaker who dares to dream, record, and share, proving that even in darkness, stories will find the light.