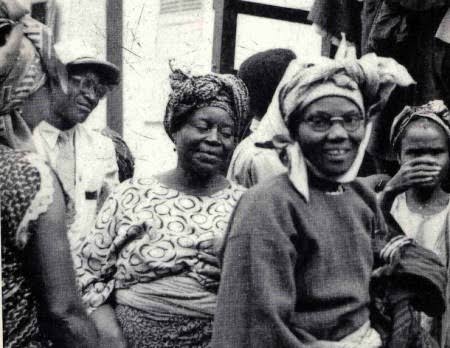

In the sweltering heat of January 1947, the streets of Abeokuta trembled under the footsteps of thousands of women. Draped in thick wrappers, their bare feet dusty from the red earth, the women were not dancing; they were protesting. They carried no weapons, only placards made of old cardboard, and sang songs that pierced the authority of the town’s most powerful man: the Alake of Egbaland, Oba Ademola II.

That day was not the beginning. It was the climax of years of anger, exploitation, and betrayal. And what happened in Abeokuta was not just about a tax protest; it was a feminist political revolution decades ahead of its time.

This is the full story of how Egba women dismantled patriarchal power—and held royalty to account.

COLONIALISM AND THE ECONOMIC STRANGLEHOLD

To understand what led to this uprising, one must begin with colonial economics. By the 1940s, Nigeria was under British colonial rule, and indirect rule had become the primary administrative model. In this system, traditional rulers were co-opted to govern on behalf of the British.

For Abeokuta, that meant the Alake—Oba Sir Ladapo Ademola II—was empowered with more centralized authority than any of his predecessors. He wielded taxation powers and judicial influence over a people who once operated under a decentralized council of chiefs and elders.

But colonialism did more than restructure power; it choked the economy. Rural producers, especially women who dominated markets in Yoruba cities, were squeezed for revenue. The British government, through the Native Authority system, imposed taxes that became heavier by the year—especially on women, even though they had no formal representation in decision-making.

By the early 1940s, the situation became unbearable. Women were being taxed without consultation, and the traditional checks and balances—especially the role of the Iyalode and the Egba Women’s Council—had been eroded.

WHO WAS FUNMILAYO RANSOME-KUTI?

At the heart of this resistance was one extraordinary woman—Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti. Born Frances Abigail Olufunmilayo Thomas in 1900, she was among the first Nigerian women to receive a formal Western education. After studying in England, she returned to Nigeria deeply committed to social justice, education, and women’s rights.

By 1944, she had founded the Abeokuta Ladies Club, a group initially focused on charity, literacy, and social welfare. But as colonial and patriarchal oppression intensified, the club transformed into the Abeokuta Women’s Union (AWU)—a radical political force with over 20,000 members, composed largely of market women, traders, and artisans.

Ransome-Kuti, influenced by socialist ideals and anti-colonial resistance, taught the women how to read and write, trained them in political organization, and prepared them for confrontation with power.

She was not just fighting colonialism. She was fighting the monarchy too.

THE ALIENATION OF THE ALAKE

The Alake, traditionally a custodian of Yoruba custom, had by the 1940s become deeply enmeshed in colonial bureaucracy. He received direct salaries from the colonial government, including allowances from taxation. To the women of Abeokuta, this made him complicit in their suffering.

Worse still, the Sole Native Authority system gave him excessive powers. Unlike precolonial Egba governance—which allowed for collective leadership by the Ogboni, the Iyalode, and the council of chiefs—the British imposed a single-ruler model.

This model effectively marginalized the role of women in local governance. Even the revered position of Iyalode (a woman leader appointed to speak for women in traditional councils) was sidelined. Taxation became arbitrary and exploitative, and market women—who formed the economic backbone of Abeokuta—bore the brunt.

HOW THE PROTESTS STARTED

By 1946, the Abeokuta Women’s Union launched a series of petitions and delegations to protest the flat tax of two shillings imposed on women. They demanded the abolition of the tax and the resignation of the Alake.

The Alake ignored them. The colonial Resident dismissed them. But they didn’t stop.

Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti and her lieutenants—like Grace Eniola Soyinka (her mother-in-law) and Chief Elizabeth Adekogbe—organized regular meetings and began educating women on civil disobedience. They adopted the tactics of Gandhi’s non-violent protests, but adapted them for Yoruba sensibilities.

The women stopped paying taxes. They stopped trading. And then, they mobilized.

THE OCCUPATION OF THE PALACE

In 1947, over 10,000 women staged a days-long sit-in at the Alake’s palace in Ake. They surrounded the building, sang derisive songs mocking his greed, and invoked Yoruba proverbs to shame him.

The songs were not just political—they were cultural weapons:

> “Alake o gb’odo gbowo l’owo aya re / ko gbo pe obinrin lo n’so ile!”

“The Alake must not take money from his wives / does he not know it is the woman who runs the home?”

They called him a “British stooge” and accused him of being “a king without his people.” Their protests brought the palace to a standstill. The colonial administration, afraid of an escalation, began investigating the women’s demands.

Meanwhile, international attention grew. The British press and some anti-colonial activists in London began following the protests. The colonial administration, fearing a public relations disaster, started to retreat.

THE ALAKE ABDICATES

In late 1948, after nearly two years of relentless protest and multiple boycotts, the pressure became unbearable. The colonial government suspended the taxation of women, and the Alake—humiliated and isolated—was forced to abdicate the throne in January 1949.

It was a moment without precedent: a Yoruba king, backed by colonial power, removed by the peaceful resistance of market women.

Oba Ademola II fled to Osogbo and remained in exile for several years. Though he was later reinstated in 1950 after reforms and reconciliation, the message was clear: royalty could be challenged—and patriarchy was not sacred.

THE LEGACY OF THE ABEOKUTA WOMEN’S REVOLT

The Abeokuta Women’s Revolt, also called the Egba Women’s Tax Revolt, was one of the most significant political uprisings in Nigeria’s colonial history. It wasn’t just a tax protest—it was a bold declaration of feminist resistance.

Key legacies include:

Formal end to women’s taxation in Abeokuta.

Greater inclusion of women in local governance.

The rise of Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti as a national figure—later becoming a founding member of the NCNC (National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons).

Inspiration for subsequent women’s protests—such as the Aba Women’s War of 1929 (in a different context), and the anti-SAP protests of the 1980s.

Funmilayo herself went on to become Nigeria’s first female political candidate and later an international voice for African liberation. She was also the mother of Afrobeat pioneer Fela Anikulapo-Kuti.

CLOSING REFLECTION: WHEN WOMEN ROARED

History is often told from the top—from the thrones of kings and the towers of colonial empires. But in Abeokuta, it was told from the ground up. From the red earth beneath the feet of women who would no longer be silenced.

The dethronement of the Alake was not just a local political event—it was the beginning of a gendered awakening. The Abeokuta Women’s Union redefined protest in West Africa, showed that traditional systems could be restructured, and paved the way for the women’s movements of the post-independence era.

In an age where feminist activism is still contested in Nigeria, the legacy of these women remains a fire waiting to be fanned. The Alake was wrong—but the women were right. And they made sure history would never forget.