In Nigeria, where royalty is measured not just in beads and ancestral shrines but also in the glint of wealth, one monarch has rewritten the code of kingship. His story is whispered with equal parts awe and disbelief: a king whose crown weighs heavier with oil barrels than coral beads, a monarch who presides over fishing villages yet commands petrol stations that stretch across the nation’s highways.

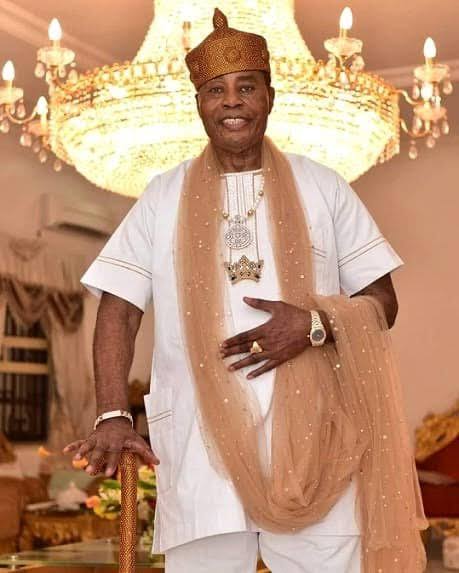

This is no ordinary tale of inheritance or palace intrigue. It is the story of Oba Fredrick Obateru Akinruntan, the Olugbo of Ugbo Kingdom in Ondo State, a man who walked the oil-soaked path of capitalism long before he sat on the ancient throne of his forefathers. While many Yoruba kings derive their authority from tradition alone, Akinruntan’s authority is gilded with billionaire status — a rare fusion of monarchy and modern business empire.

To meet him is to encounter a paradox: a traditional ruler who sits in council with chiefs by day, and a tycoon who negotiates oil deals by night. In his Rolls Royce Phantom, customized to rival that of the late Queen Elizabeth II, he rides not only as a king but also as a businessman who built one of Nigeria’s most successful independent oil companies. His story is a metaphor for Nigeria itself — a nation where ancient crowns rest on modern oil fields, where tradition and wealth constantly negotiate space.

Yet beneath the sheen of his empire lies a more compelling narrative: how a boy who grew up by the rivers of Ilaje, helping his family in fishing trade, came to wield a billionaire’s scepter. His rise did not come through inheritance, nor through state politics, but through an audacious foray into oil at a time when few dared to challenge multinational corporations.

From Riverine Childhood to Palace Gates

Fredrick Obateru Akinruntan’s early life was shaped by the salty winds of the Atlantic and the modest rhythms of Ilaje communities in Ondo State. The Ugbo Kingdom, where he was born in 1950, is a cluster of fishing settlements carved out by waterways, where boats served as both transport and livelihood. For centuries, the people lived by the sea, building canoes, casting nets, and sustaining themselves on fishing trade.

Akinruntan’s family was not wealthy by palace standards. His childhood bore none of the extravagance that would later define his reign. Instead, he grew up observing the discipline of survival — watching men brave the tides for fish, and women trading the catch in nearby markets. The Ilaje, renowned for their maritime skills, passed down traditions of resilience and enterprise, lessons that would shape his outlook on business.

Unlike many Nigerian monarchs whose childhoods are steeped in palace rituals, Akinruntan’s youth was practical, even austere. He received his early education in Ondo State, but formal schooling was limited. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, when Nigeria was rebuilding after civil war and oil was emerging as the new backbone of the economy, Akinruntan’s attention turned to commerce. He started small: trading goods, engaging in local businesses, and testing his entrepreneurial instincts.

But he was not content with the limitations of small trade. The vision that stirred within him was larger — tied to the same oil that was transforming Nigeria into Africa’s largest producer. In the bustling cities of the southwest, especially Ibadan and Lagos, he saw the growing dependence on petroleum products. Gasoline was not just a commodity; it was becoming the lifeblood of transport, commerce, and industry. If Nigeria’s fortunes lay in oil, why shouldn’t his?

Crude Awakening: The Rise of Obat Oil

In 1981, Akinruntan made a move that would alter the course of his life: he founded Obat Oil and Petroleum Limited, with a single petrol station in Ibadan. At the time, few indigenous entrepreneurs dared to challenge the oil marketing sector, which was dominated by global giants like Mobil, Texaco, and Shell. Fuel distribution was tightly controlled, and the downstream sector was capital-intensive.

But Akinruntan saw opportunity where others saw monopoly. He understood that Nigeria’s rapidly urbanizing population would always need fuel, and that independent marketers could bridge the gap in areas underserved by multinationals. His first station became a model of efficiency and customer loyalty, and from that seed, an empire began to sprout.

The early 1980s were not kind to small businesses. Nigeria’s economy swung between oil boom and austerity, and structural adjustment policies made access to capital difficult. Yet Obat Oil survived, and by the 1990s, it had grown into one of Nigeria’s largest indigenous oil companies. Its retail network expanded across the country, planting the “Obat” brand name in cities, highways, and towns.

Akinruntan was no ordinary businessman. He built his company not just on profit margins but on visibility — ensuring that Obat Oil stations became symbols of reliability. Where state refineries faltered and scarcity bit into daily life, Obat’s distribution networks provided respite. He carved a niche as the king of independent marketers, even before he wore a crown.

His foresight extended beyond petrol stations. In later years, Obat Oil would acquire massive oil storage facilities, including one of the largest tank farms in Lagos with a capacity of over 65 million liters. This positioned his company as a critical player in Nigeria’s downstream sector, supplying fuel not just to motorists but to entire regions.

By the dawn of the new millennium, Obat Oil was a household name, and its founder had become one of the wealthiest businessmen in the southwest. Yet, destiny had a different crown in store. In 2009, Fredrick Obateru Akinruntan was chosen as the Olugbo of Ugbo Kingdom, returning him to the ancestral throne of his forefathers.

And so, the boy from the rivers who once watched fishermen mend their nets now wore the beaded crown of his people — with an oil empire in his hands.

The Throne and the Pump

In March 2009, the Ugbo people crowned Fredrick Obateru Akinruntan as the Olugbo of Ugbo Kingdom, a coronation that bridged centuries of history with the realities of modern power. The ceremony, filled with chants, masquerades, and processions, was as traditional as any Yoruba enthronement. Yet, when the new king sat on the beaded throne, he carried more than ancestral authority. He carried the financial clout of a billionaire oil magnate.

This duality set him apart from his peers. While other monarchs relied heavily on stipends from state governments and contributions from wealthy subjects, Akinruntan entered the palace with independent resources that far exceeded what courtiers could imagine. His oil wealth gave him a leverage few traditional rulers could dream of: the ability to fund palace activities, launch community projects, and assert influence in state politics without bowing to financial dependence.

The Olugbo throne itself is ancient, tied to the history of the Ilaje and their maritime settlements. Historically, Ugbo kings were custodians of sea routes, fishermen’s protectorates, and spiritual heads of a community defined by water. Yet the throne had often been overshadowed by the more famous Yoruba monarchies — the Ooni of Ife, the Alaafin of Oyo, the Oba of Benin. In 2009, however, the Olugbo throne drew unprecedented attention. The reason was simple: its occupant was one of Africa’s few monarchs with Forbes-listed billionaire wealth.

This shift was profound. It meant that the Olugbo was no longer just a traditional custodian; he was also a player in Nigeria’s economic elite. His throne carried symbolic beads, but also bank statements running into billions. Courtiers accustomed to measuring a king’s generosity by the number of goats or bags of rice distributed during festivals now found themselves under a monarch who could donate millions at a stroke, or roll up to the palace in a fleet of luxury cars.

The palace of Ugbo became a fusion of ancient Yoruba tradition and modern opulence. Chiefs still carried out rituals, women sang praise chants, and masquerades performed ancestral rites. But alongside these traditions stood the trappings of oil wealth: SUVs lined in courtyards, imported marble floors, and satellite communications connecting the king to Lagos, London, or Dubai.

What did it mean, then, for a community historically reliant on fishing to have a monarch who owned oil depots? It meant, above all, that the relationship between palace and people was redefined. No longer was the king just a spiritual figure; he became a living symbol of modern success, proof that Ugbo indigenes could sit at the global table of wealth.

Palatial Wealth: The Billionaire Crown

The world outside Ugbo took notice when Forbes Africa’s 2014 Rich List placed Oba Akinruntan among the richest kings on the continent, estimating his fortune at around $300 million. The figure was contested — as is often the case with opaque African wealth — but the symbolism mattered more than the exact digits. It was a recognition that Nigeria’s traditional ruler had crossed into the billionaire’s club, a rare achievement in a country where monarchies had lost much of their economic clout to modern politics.

The ranking placed him alongside Africa’s better-known business monarchs, such as King Mohammed VI of Morocco, whose billions came from investments spanning real estate, banking, and phosphate mining. In Nigeria, he stood out against fellow Yoruba monarchs: the Ooni of Ife, revered for spiritual primacy; the Alaafin of Oyo, remembered for historical grandeur; and the Oba of Benin, custodian of ancient dynasties. Yet none of them commanded oil wealth in the way the Olugbo did.

This visibility came with new narratives. Newspapers splashed stories of a monarch who not only sat in palace meetings but also controlled vast oil tank farms in Lagos. Television crews documented his appearances at industry events, where he was addressed not just as “Kabiyesi” but as “Chairman.” For the first time in modern Nigeria, the image of a king and that of a boardroom executive fused into one personality.

The paradox was not lost on observers. Kingship in Yoruba tradition is sacred, demanding humility, patience, and communal focus. Yet billionaire wealth often thrives on competition, ambition, and accumulation. How could these two worlds coexist? For Akinruntan, the answer was clear: wealth did not diminish his kingship; it amplified it. The more successful he was in business, the more prestige he brought to his throne.

There were critics, of course. Some argued that excessive focus on wealth undermined the moral authority of traditional rulers, making them appear as capitalist entrepreneurs rather than cultural custodians. Others saw in Akinruntan’s reign an inevitable evolution of Nigerian royalty — one where kings could no longer rely on outdated tribute systems but had to carve out modern economic relevance.

For the Ugbo people, however, the billionaire crown became a source of pride. It was said in fishing villages that their monarch was no longer just “Kabiyesi Olugbo,” but also “the king of oil.” Young people saw in him an aspirational figure: proof that even from a remote kingdom, one could build an empire rivaling Lagos tycoons.

The billionaire crown also came with expectations. A king with such resources could not afford to be stingy. His wealth was seen as a collective blessing, meant to spill over into community development. Festivals, scholarships, and infrastructural projects became avenues for redistributing his fortune. And though the gap between the palace and the courtiers widened, the symbolic power of a wealthy monarch endured.

Oil, Power, and the Yoruba Crown

Oil wealth reshaped not only the palace but also the very meaning of Yoruba kingship. For centuries, the Yoruba crown had symbolized ancestry, spirituality, and cultural continuity. It was built on myths of Oduduwa, lineages of Oyo, and traditions of Ife. Wealth, though important, was secondary to sacred legitimacy.

But in the 21st century, legitimacy alone was no longer enough. In a society where politicians flaunted billions and businessmen commanded international empires, monarchs without economic backing risked irrelevance. Into this reality stepped Oba Akinruntan, whose oil empire provided the financial muscle that kingship alone could not.

Oil became his modern scepter. Where other monarchs drew power from historical prestige, Akinruntan drew it also from the market forces of petroleum. His subjects bowed not only to his ancestral authority but also to his status as a major employer and benefactor. In councils of Yoruba Obas, where rivalries often centered on hierarchy and tradition, his oil wealth gave him a unique edge.

Yet, this blend of oil and crown also raised questions. Could a king’s business interests compromise his neutrality in disputes involving land or resources? Could the pursuit of profit distract from the sacred duties of monarchy? These questions followed Akinruntan, as critics pointed to the delicate line between palace and pump.

Still, the Yoruba tradition has always adapted to changing times. Centuries ago, kings ruled with warriors and horsemen; today, they rule with influence, philanthropy, and visibility. In that sense, Akinruntan’s oil crown was simply another evolution. The palace was no longer sustained by tributes of yam and palm wine, but by dividends and fuel receipts.

For the courtiers, the irony was unavoidable. Many still lived modestly, their incomes derived from fishing or petty trade, while their monarch flew in private jets and sat at oil conferences. The phrase “more oil than courtiers” became not just metaphor but fact. It underscored the widening gulf between ancient communal expectations and modern capitalist realities.

And yet, the Olugbo remained their king. His oil empire might place him among Nigeria’s richest, but in festivals he still danced to the same drums, poured libations to the same ancestors, and wore the same coral beads as his predecessors. In that paradox lay the essence of his reign: a billionaire crown that carried both crude oil and cultural duty.

The Rolls Royce Phantom and the Symbolism of Excess

In 2012, Nigeria gasped when Oba Akinruntan unveiled his Rolls Royce Phantom 2012 edition, customized to match that of the late Queen Elizabeth II. The car — with its gleaming grill, handcrafted interior, and personalized license plates — was not merely transportation. It was a statement.

Few Nigerian monarchs had ever flaunted such open extravagance. While it was common for kings to ride in convoys of SUVs or ceremonial horses, a Rolls Royce Phantom in a riverine community was an anomaly. The symbolism was not lost on journalists: here was a monarch who had transcended the rustic image of traditional royalty and placed himself in the global league of wealth display.

For Akinruntan, the car was both personal indulgence and cultural metaphor. It projected his wealth beyond palace walls, announcing that a king of Ugbo could drive the same luxury automobile as the British monarch. It was a declaration of parity — that Yoruba royalty, often marginalized in modern narratives, could stand shoulder-to-shoulder with global monarchies.

The Rolls Royce quickly became a cultural icon. At festivals, when it pulled up to palace grounds, villagers crowded to glimpse the machine. For many, it was the closest they would come to luxury of such magnitude. Children whispered tales of their king who rode in a car built for queens. Praise singers wove the Phantom into their oríkì, hailing him as the monarch whose wheels rivalled the crown of England.

Critics, however, were less impressed. In a nation battling poverty and infrastructural decay, the Rolls Royce was interpreted by some as a symbol of excess. Why flaunt wealth in a land where courtiers struggled to afford school fees or daily meals? Wasn’t monarchy meant to embody communal humility?

But wealth and symbolism are inseparable in kingship. Just as coral beads once signaled authority and elephant tusks symbolized prosperity, in the 21st century, luxury cars became the new markers of power. For Akinruntan, the Rolls Royce Phantom was not mere excess; it was a crown on wheels.

Inside the Ugbo Kingdom

Nestled along the coast of Ondo State, Ugbo is a cluster of fishing villages and riverine settlements, bound together by waterways that stretch into the Atlantic. The land is rich in culture but limited in infrastructure. Wooden boats glide across creeks, children chase each other on sandy paths, and women dry fish in sun-scorched courtyards.

The kingdom’s history is tied to the sea. For generations, its people have lived as fishermen, divers, and boat builders. Their economy is local, their rhythm dictated by tides and seasons. The arrival of a billionaire monarch into this setting created a dissonance.

In the palace, imported chandeliers lit up marble floors. Chiefs wore expensive fabrics during council meetings. Guests dined on meals prepared in kitchens stocked with imported goods. Yet, just beyond the palace gates, villagers still relied on boreholes for water and kerosene lamps for light.

This contrast reflected a broader Nigerian reality: islands of wealth amid oceans of poverty. For the Ugbo people, however, Akinruntan’s wealth was double-edged. On one hand, it made them proud that their monarch could compete with global elites. On the other, it raised expectations that he should transform their living conditions.

To his credit, the Olugbo invested in community development. He supported education initiatives, funded scholarships, and contributed to local festivals. His palace became a hub of cultural revival, ensuring that despite modern trappings, the ancestral traditions of Ugbo were preserved. Yet the sheer scale of poverty meant that such efforts were often seen as drops in a vast ocean.

The mystery deepened: how could a king own oil depots worth billions while his subjects struggled to fuel their lamps? It was a question whispered in markets and debated in newspapers. The answer was complex, tied to Nigeria’s broader structural inequalities and the limits of individual philanthropy.

But one thing remained clear: the Ugbo Kingdom had never been more visible. Before Akinruntan, few outside Ondo State knew much about the community. After his rise, Ugbo became synonymous with oil wealth and a billionaire king.

The Business of Being King

For Oba Akinruntan, kingship did not mean stepping away from the corporate world. Instead, it meant balancing two identities: the custodian of ancestral traditions and the chairman of an oil empire.

Running Obat Oil from the palace required both delegation and oversight. His children and trusted associates took charge of day-to-day operations, but the king remained deeply involved in strategic decisions. The company’s Lagos tank farm, with its capacity of over 65 million liters, positioned Obat Oil as a critical player in Nigeria’s petroleum distribution. This tank farm alone gave him leverage in negotiations with the government, the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC), and other independent marketers.

Yet, being both king and businessman carried risks. Land disputes, common in the oil-rich Niger Delta, often intersected with palace authority. As Olugbo, Akinruntan mediated conflicts involving land ownership, even as his company pursued expansion. Critics accused him of leveraging his throne to advance business interests; supporters countered that his success gave him the capacity to uplift his people.

Navigating this duality required diplomacy. In council meetings with fellow Yoruba monarchs, he was expected to speak as a custodian of tradition, not as a tycoon. In boardrooms with oil marketers, he was expected to negotiate as a businessman, not as a king bound by ancestral oaths. Moving seamlessly between these worlds became his unique skill.

It was also a reminder that monarchy in modern Nigeria could not remain insulated. Kings had to find relevance in politics, business, or social influence. Some embraced politics directly, others leaned on cultural authority, but Akinruntan chose oil. His empire became the financial engine that powered his palace, ensuring that unlike many monarchs, he was not at the mercy of government allocations.

The business of being king also extended to symbolism. Every public appearance was calculated: the Rolls Royce at festivals, the elaborate palace receptions for oil executives, the grand displays of philanthropy. These gestures reinforced his image as both monarch and mogul, blurring the line between cultural custodian and capitalist monarch.

And so, the Olugbo’s reign stood as a case study in Nigeria’s evolving monarchy: a throne dipped in oil, balancing ancestral duty with corporate ambition.

Legacy of Oil, Legacy of Crown

Every monarch, no matter how wealthy, must confront the question of legacy. For Oba Akinruntan, the question carries dual weight: what will become of Obat Oil, and how will the Olugbo throne evolve under his lineage?

Obat Oil has grown into one of the most prominent indigenous oil companies in Nigeria, anchored by its Lagos tank farm and retail network. Its continuity depends on succession planning, and Akinruntan has ensured that his children are deeply involved in the business. Like many dynasties, the empire’s survival will rest on whether heirs can balance loyalty to family, respect for tradition, and the ruthlessness of corporate competition.

On the cultural side, the Olugbo throne has gained unprecedented visibility during his reign. He repositioned a once relatively obscure throne into national discourse, making Ugbo synonymous with wealth and modern royalty. But legacy is fragile. Future generations will ask: did the billionaire crown serve the people? Did it translate into long-term transformation for the fishing villages of Ilaje? Or was it a chapter of spectacle, remembered more for Rolls Royces than reforms?

There is also the delicate matter of succession in Yoruba monarchies. Thrones are rarely straightforward; they involve competing royal lineages, political maneuvering, and community acceptance. When Akinruntan eventually passes the baton, the next Olugbo will inherit not just a palace, but the shadow of a billionaire reign. The comparison may empower or burden them, depending on how history frames the current monarch’s achievements.

His legacy, therefore, lies at a crossroads: he is both a symbol of possibility and a reminder of Nigeria’s contradictions. A king who proved that ancient thrones could coexist with billion-dollar empires, yet whose reign underscored the enduring gaps between palace wealth and communal poverty.

Concluding Lens: The Crown Dipped in Oil

Oba Fredrick Obateru Akinruntan’s life is a metaphor for modern Nigeria. He rose from the riverine simplicity of Ugbo to the marble corridors of oil wealth, building an empire that placed him among Africa’s richest monarchs. He ascended a throne centuries old, yet carried with him the swagger of a corporate mogul. His Rolls Royce Phantom, his oil depots, his Forbes ranking — all these are emblems of a king whose crown is soaked in crude.

But beyond spectacle lies paradox. For his courtiers, the billionaire crown is both pride and puzzle: how to reconcile their modest livelihoods with a monarch who commands more oil than they could ever imagine. For Nigeria, his reign is both inspiration and caution: proof that tradition can adapt to modern wealth, but also a reminder that inequality persists even under the most prosperous crowns.

History will remember Oba Akinruntan not just as the Olugbo of Ugbo, but as the king who rewrote what it meant to wear beads in the age of oil. His story is neither purely royal nor purely capitalist — it is both, fused into one. A monarch in coral regalia, a tycoon in tailored suits, a fisherman’s son who became the custodian of oil and crown.

And so, when the history of Nigeria’s 21st-century monarchs is written, one image will stand apart: a king whose palace echoes with ancestral chants, even as the hum of oil tank farms roars in the distance. A king whose crown glistens not just with coral and gold, but with the sheen of crude oil — heavier, brighter, and more complex than any his courtiers had ever seen.