On the eve of Nigeria’s independence, Lagos was a city caught between two heartbeats. One belonged to the colonial order—rigid, watchful, fraying at the seams. The other was the restless pulse of a nation waiting to breathe on its own, uncertain of what freedom might demand. The streets carried whispers of celebration, but also the weight of unfinished reckonings, as if the air itself understood that political change could never erase the shadows left behind.

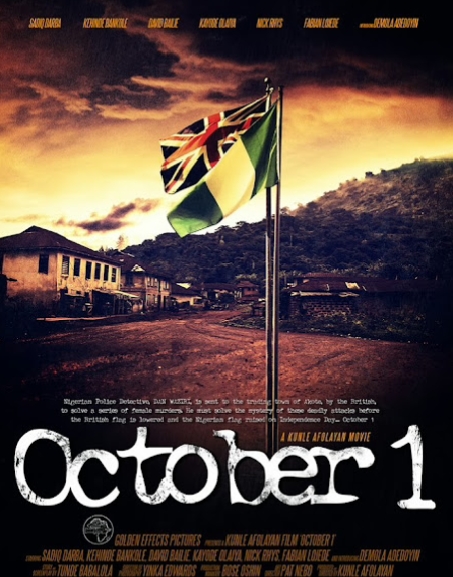

It is in this twilight—neither fully colonial nor yet sovereign—that October 1 takes root. The film does not open with fireworks or speeches, but with unease. Its power lies in how it threads suspense into history, using silence, setting, and faces etched with conflict to show that independence is never just a date on the calendar—it is a confrontation with buried truths.

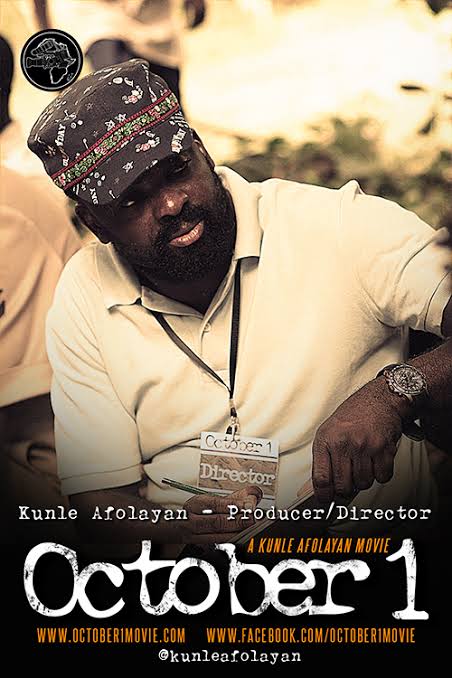

Kunle Afolayan, the filmmaker, builds his story from these tensions, crafted a work where every scene mirrors the fragile state of a country in transition. To watch the film is not merely to follow a plot, but to step into an atmosphere heavy with both anticipation and dread.

Colonial Lagos: Empire’s Shadow Over the Lagoon

Lagos in the twilight of the 1950s was more than a capital city—it was the nerve center of a colonial experiment nearing its expiration. The lagoon shimmered under the sun, its waters carrying both the commerce of empire and the quiet defiance of a people who knew freedom was close. British officers still patrolled government houses, files stamped with the Crown’s insignia still dictated daily life, yet the air was restless, filled with the murmurs of markets, rallies, and prayers that signaled a country ready to step beyond foreign rule.

Colonial Lagos lived in contradiction. On one side were the manicured lawns of Ikoyi, the stiff routines of administrators, and the clubs where empire congratulated itself. On the other were the bustling quarters of indigenous life—Balogun markets alive with Yoruba traders, mosques calling the faithful at dawn, the cries of children running along streets still unpaved. The city was divided, yet inseparably bound, a place where colonial authority pressed down but could not smother the pulse of an emerging nation.

This Lagos—half-controlled, half-aspiring—sets the stage for the story of October 1. The film is not just about a village investigation but about the shadow cast by empire, the fractures it left behind, and the uneasy birth of a new identity at the moment of independence.

October 1: A Cinematic Lens on History

Kunle Afolayan’s October 1 is more than a thriller; it is a meticulously crafted exploration of Nigeria’s complex path to independence. Released in 2014, the film reflects Afolayan’s signature approach: blending historical consciousness with suspense-driven storytelling, framed through the intimate human experiences of his characters. His direction is deliberate, measured, and steeped in attention to period detail. Lagos, the villages, the clothing, the vehicles, even the subtleties of speech, are all curated to evoke a 1960 Nigeria poised on the precipice of self-rule.

Afolayan’s camera does not merely observe; it participates. Wide shots of colonial buildings contrast with close-ups of characters’ expressions, allowing viewers to navigate the tension between the public and private, the societal and personal. Music, largely diegetic, underlines suspense without overwhelming it, while lighting casts literal and figurative shadows—both on the streets of Lagos and in the psychological landscape of Akote village. The film’s narrative is as much about what is unseen as what is revealed. It is a story built on ambiguity, the weight of history, and the moral complexity of human behavior.

By situating the story in 1960, Afolayan allows October 1 to operate on multiple levels. It is a historical thriller, a cultural study, and a meditation on morality. The impending independence functions as both backdrop and narrative device, reminding audiences that the political freedom of a nation does not automatically resolve the intimate tragedies, ethical ambiguities, or societal contradictions that define human experience. Through this lens, the city and village, the inspector and the villagers, the living and the dead, all become reflections of a nation negotiating its own shadow.

Main Cast of October 1 (2014)

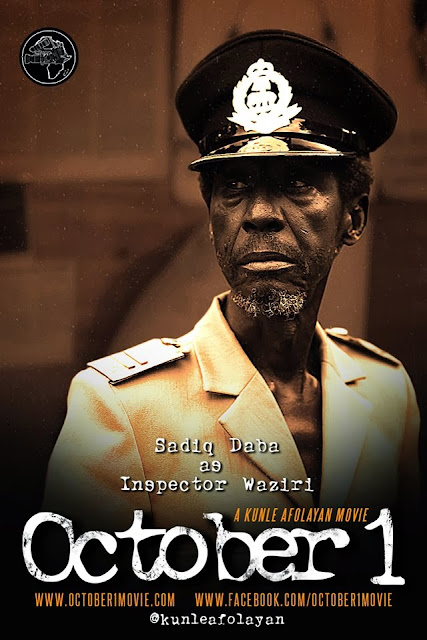

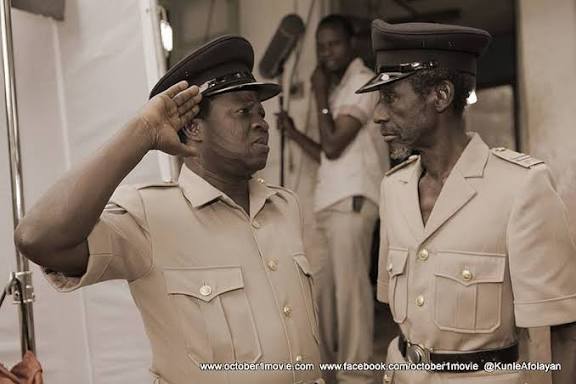

Sadiq Daba as Inspector Danladi Waziri

A seasoned Northern Nigerian police officer dispatched to investigate a series of murders in a remote Western village.

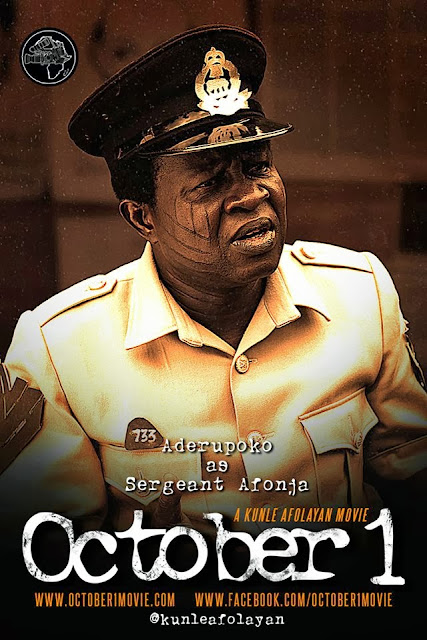

Kayode Olaiya as Sergeant Sunday Afonja

The inspector’s loyal assistant, aiding in the investigation with diligence and support.

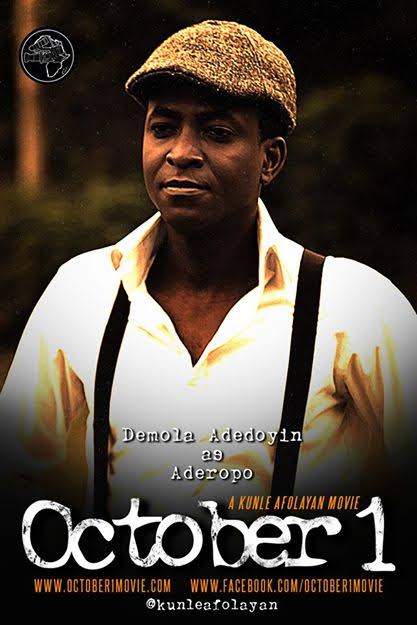

Ademola Adedoyin as Prince Aderopo

A key figure whose background and actions are central to the unfolding mystery.

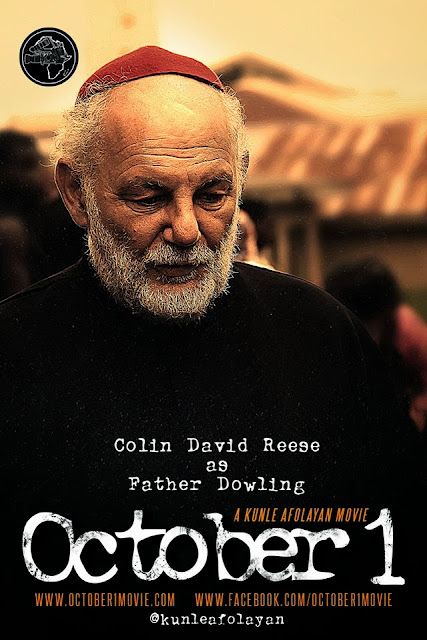

Colin David Reese as Father Dowling

A religious figure whose interactions with the community are pivotal to the narrative.

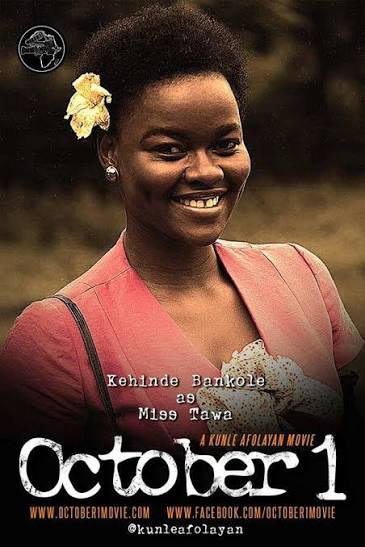

Kehinde Bankole as Miss Tawa

A significant character whose relationship with Inspector Waziri deepens the emotional layers of the story.

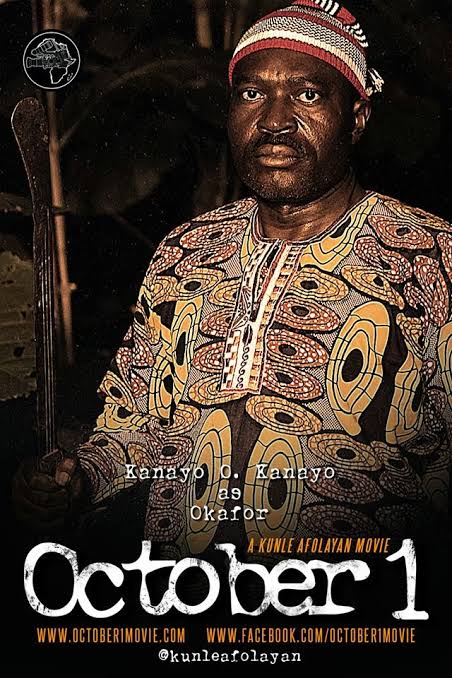

Kanayo O. Kanayo as Okafor

A character whose background and actions are integral to the unfolding mystery.

Characters: The Human Core of October 1

At the heart of Afolayan’s direction are characters whose depth elevates the film beyond procedural thriller. Every individual serves as a node in a network of cultural, historical, and moral significance.

I) Inspector Danladi Waziri

A Northern Nigerian officer, Danladi embodies discipline, methodical intelligence, and moral reflection. His identity situates him both as a participant and an observer: trained under colonial policing standards, yet guided by faith and ethical reasoning. Danladi is meticulous in his investigative approach, but Afolayan emphasizes that procedural expertise alone cannot untangle the complex social and cultural realities of Akote. His presence underscores the tension between law and local morality, outsider and insider, reason and tradition.

II) Chief Ayodele

The village chief represents authority tempered by tradition. He is a custodian of Yoruba culture and social order, yet even he cannot fully control the currents of fear, secrecy, and grief that permeate his community. Through Ayodele, Afolayan examines the limitations of traditional power when confronted with both human depravity and the ethical complexities of cultural norms.

III) Villagers

The inhabitants of Akote are not merely background figures; they are the lifeblood of the narrative. Farmers, merchants, mothers, fathers, and children—all contribute to a sense of communal intimacy while also embodying the secrets and moral compromises that sustain it. Afolayan’s direction gives them space to breathe: small gestures, subtle reactions, and whispered conversations convey layers of social and historical tension that formal dialogue could never capture alone.

IV) Victims and Women of Akote

The young women whose disappearances drive the investigation are depicted with dignity and humanity. They are not plot devices but embodiments of innocence, vulnerability, and the consequences of systemic failures—both societal and familial. Their presence, absence, and the way the community responds to their fates illuminate gender dynamics, patriarchal pressures, and the often-unspoken moral debts of the village.

V) Supporting Figures

Figures like Dr. Adeleke, the medical examiner, and Suleiman, Danladi’s assistant, function as bridges—between modernity and tradition, observation and action, North and South. They offer insight, provide narrative momentum, and highlight cultural collisions while remaining deeply human and contextually grounded.

Afolayan’s careful construction of characters ensures that each is morally and psychologically credible. The film does not rely on caricature or simplified conflict; instead, it explores how individuals navigate personal ethics, communal expectation, and historical forces beyond their control. This humanization transforms October 1 from a simple murder mystery into a nuanced exploration of culture, history, and morality.

The Plot Unfolds: Inspector Danladi Enters Akote

The journey from Lagos to Akote is both literal and symbolic. Trains rumbled through landscapes that shifted from urban bustle to rural calm, carrying Danladi into a world removed from colonial oversight yet deeply entwined with its consequences. The journey itself is a study in contrast: the disciplined order of the train and station juxtaposed against the sprawling, unplanned rhythms of the countryside. Villagers lean over tracks, curious, wary; the inspector observes quietly, recording impressions with the diligence of a man whose profession demands both patience and precision.

Afolayan’s camera lingers on the subtleties of the landscape—the shadows of mangrove trees, the reflection of sunlight on shallow rivers, the smoke curling from village fires. These are not mere scenic interludes; they establish mood and foreshadow the moral and human darkness that will define Akote. Even before setting foot in the village, the audience senses that this journey is not only about travel but about entering a morally and culturally complex world.

I) Arrival in Akote: A Village of Secrets

Akote itself is a character in the story. The dusty streets, low compound walls, and palm-fringed courtyards convey both warmth and restraint. Villagers watch Danladi with a mixture of respect, curiosity, and suspicion. Here, the tension between outsider authority and indigenous social order becomes palpable.

Chief Ayodele welcomes the inspector with formal courtesy, yet his eyes betray the subtle power dynamics of a man responsible for a community rife with secrets. Villagers move in patterns that are both habitual and cautious; their glances, gestures, and silences speak volumes. Afolayan’s framing emphasizes these micro-moments, showing how human behavior, unspoken agreements, and communal morality can shape both perception and action. Every door that closes, every whispered conversation, every child who retreats into the shade contributes to the tension, reminding viewers that the true story of Akote lies as much in its absences as in its visible life.

II) Investigation Begins: Patterns and Shadows

The murders that brought Danladi to Akote are not merely crimes—they are catalysts for exploring morality, tradition, and the limitations of law. Each crime scene is meticulously staged: rooms left undisturbed, the absence of the victims’ voices echoing in empty spaces, the subtle traces that only a trained eye can detect.

Danladi’s methodical approach contrasts with the villagers’ intuitive, culturally embedded knowledge. He questions elders, examines traces, and cross-references statements, always aware that truth in Akote is layered beneath both fear and social convention. Villagers sometimes cooperate, sometimes obstruct—whether out of fear, shame, or tacit complicity. Afolayan uses this tension to heighten suspense, showing that procedural investigation alone cannot untangle the web of communal secrecy and historical trauma that envelopes the village.

III) Daily Life and Cultural Intersections

Between investigation sequences, the film immerses viewers in Akote’s daily life. Markets bustle with traders, children run through dusty lanes, and households follow rhythms that blend practical labor with spiritual observance. Afolayan’s camera captures these vignettes with empathy and precision, humanizing every inhabitant while reminding the audience of the weight of cultural context.

Religious practices, family hierarchies, and communal rituals are depicted with nuance. The inspector, as an outsider, observes and learns, often misinterpreting cues but gradually developing insight. These sequences are more than narrative filler; they emphasize the collision of modern law enforcement with local knowledge and morality, highlighting how justice is not simply codified but lived, negotiated, and sometimes deferred by human discretion.

IV) Rising Tension: The Investigation Deepens

As murders continue, the tension tightens. The camera lingers on abandoned compounds, shadows in narrow streets, and the reactions of villagers to one another. Suspicion spreads like wildfire; neighbors question neighbors, secrets slip into public view, and the moral weight of the village becomes unbearable.

Danladi’s methodical approach is increasingly tested. His patience and observation reveal both the vulnerability of the victims and the moral compromises of those around them. Each interview, each observation, each carefully noted detail brings him closer to truth while also deepening the moral complexity of the narrative. Afolayan’s direction ensures that suspense is never merely procedural; it is human, emotional, and culturally resonant.

V) Climax: Confrontation and Revelation

Without revealing the murderer outright, the film builds toward a climax where the inspector confronts the convergence of personal trauma, communal secrecy, and historical consequence. The cinematography emphasizes darkness and isolation, reflecting both the literal nighttime investigation and the figurative moral darkness the village harbors. Tension peaks not only in the physical confrontations but in the ethical reckonings: who is responsible, what is justice, and how does a society reconcile past and present failings?

Afolayan’s direction here is precise: pacing slows and quickens in tandem with the inspector’s discoveries, sound design punctuates suspense without overwhelming, and every frame carries moral weight. The village becomes a mirror, reflecting human frailty, collective responsibility, and the lingering shadows of colonial and patriarchal structures.

Resolution: Independence Day as Reflection

The narrative resolves against the backdrop of October 1, 1960—the day Nigeria declares independence.

Celebration and political triumph contrast sharply with the personal and communal reckonings that the inspector leaves behind. Danladi departs, carrying the weight of his experiences, while the village continues its life, transformed yet burdened by the moral lessons of the investigation.

Independence, Afolayan reminds us, is not only political; it is ethical and social. A nation may gain sovereignty, but human behavior, historical trauma, and cultural complexity remain unresolved. The juxtaposition of national celebration with private darkness creates the film’s lasting resonance, allowing viewers to reflect on the interplay between history, morality, and human nature.

Cultural and Historical Resonance

October 1 succeeds because it intertwines suspenseful storytelling with cultural and historical authenticity. The film immerses viewers in Yoruba village life, Northern-Southern dynamics, colonial legacies, and the anxieties of a nation approaching independence. Characters are fully realized, human, and morally complex, providing insight into both personal and collective behavior. Danladi’s navigation of law, ethics, and cultural understanding highlights the tension between imported authority and indigenous moral frameworks—a tension that remains relevant in postcolonial discourse today.

Moreover, Afolayan’s direction underscores the universality of human fallibility. Villagers, authorities, and victims alike are not mere archetypes; they are living embodiments of decisions, consequences, and historical circumstance. By humanizing every participant, the film avoids sensationalism, instead creating empathy, tension, and reflection. It is through this lens that October 1 becomes more than a thriller; it is a study of society, history, and morality.

Conclusion: Shadows That Endure

As the credits roll, the audience is left with lingering questions: What is justice in a society negotiating secrecy and morality? How do history, culture, and colonial legacy shape human behavior? Inspector Danladi’s journey, framed against the threshold of independence, embodies both the promise and the limits of order, law, and ethical action.

Kunle Afolayan’s October 1 does not offer simple answers. Instead, it invites viewers to consider the shadows that persist long after political victories, the interplay between human frailty and societal expectation, and the moral reckonings that continue to shape individual and collective life. The film’s resonance lies not only in its suspenseful plot but in its deep engagement with culture, history, and the human heart—a reflection as relevant today as it was in 1960.

Through meticulous direction, immersive settings, and fully realized characters, Afolayan crafts a narrative that is both historically grounded and timelessly human. The darkness Danladi confronts in Akote is mirrored in every society grappling with the legacy of the past, the moral weight of the present, and the uncertainties of the future. In this interplay of shadow and light, October 1 secures its place as a landmark in Nollywood cinema and a profound meditation on independence, morality, and human nature.