Night falls over Lagos like a heavy curtain, swallowing streets and alleys in darkness. The air hangs thick with anticipation, punctuated by distant shouts, the muted rhythm of a lone drum, the faint creak of a boat against the lagoon. Even as the city slumbers, something stirs. Footsteps echo where no one is, shadows twist and sway beyond lamplight, and the wind seems to carry voices that do not belong entirely to the living.

In the quiet hours, Lagos speaks in a language few can understand. The sound is not loud, but it exists in the spaces between movement: the rustle of palm fronds, the clatter of a shutter, the murmur of the tides. And there are those who hear it. Those who pause and listen, attuned to rhythms invisible to most. Among them was a man whose footsteps were as silent as the secrets he would one day reveal—Israel Kolawole Dairo.

He moved through the city streets like a shadow himself, eyes alert, ears catching the subtlest disturbances in the night. Some said that when he played, the city leaned closer, as if recognizing an interpreter it had long awaited. What he heard in the darkness was never fully explained: sometimes laughter, sometimes sorrow, sometimes echoes that seemed to belong to the past itself. Listeners could feel it—something beyond ordinary sound, something that lingered even after the music had ended.

And then there were the nights when people swore the city’s pulse changed. Notes hung longer than they should, rhythms twisted in ways that defied expectation, and the hair on one’s arms would rise. Those who had witnessed it later spoke in hushed tones, uncertain whether it was memory, imagination, or something else entirely.

Lagos slept, yet it was awake in ways that could not be named. And in the midst of the quiet streets, some claimed that a presence moved among the sounds—a mysterious force that whispered through the city, unseen, only felt. It was here, in this tension between the ordinary and the unexplainable, that the story begins: a story of music, memory, and the subtle orchestration of ghosts.

Listening to the Invisible: Young Dairo in Ibadan

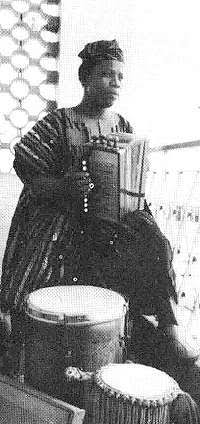

Israel Kolawole Dairo was born in 1930 in Ibadan, a city alive with rhythm long before he first held a drumstick. The streets themselves were an orchestra: the tap of sandals on dirt roads, the clanging of pots in courtyard kitchens, the whispers of the wind through palm fronds. In his household, sound was constant—family gatherings where elders recited praise poems, neighbors performed traditional chants, and children drummed improvisational rhythms on any available surface. For Dairo, these were not background noises; they were lessons, raw and unstructured, teaching him that every sound had a place, a voice, a meaning.

From a young age, Dairo displayed an unusual sensitivity. While other children played aimlessly, he would pause, listening. He could replicate the cadence of a vendor’s cries, the subtle inflections of a lullaby, or the tonal patterns of the talking drum. This instrument, capable of mimicking the inflections of speech, fascinated him. Its rhythms could convey both information and emotion, a language that was both literal and poetic. To Dairo, it was as if the drum carried invisible presences, shadows of human experience waiting to be understood.

School lessons were often secondary to the lessons of sound. Dairo observed the cadence of his teachers’ speech, the way the wind altered the tone of a doorway’s creak, the rhythm of footsteps echoing in courtyards. Each observation became a fragment of musical understanding. By adolescence, he had begun experimenting: layering indigenous percussion with Western instruments like the guitar and piano, seeking a synthesis that could capture the full spectrum of what he heard. These experiments were not random; they were attempts to translate life itself into melody, to give form to the invisible patterns he sensed in the world.

Beyond technical exploration, Dairo immersed himself in Yoruba oral tradition. He memorized praise poems, historical tales, and proverbs, realizing that rhythm and narrative were inseparable. Music, he understood, was not merely entertainment—it was memory, history, and identity encoded in sound. Performing in local gatherings, he drew the attention of elders and peers alike. What set him apart was not only skill, but empathy: he could listen to a room and reflect its spirit through rhythm, translating joy, grief, and tension into something audible.

It was in these formative years that the seeds of his future mastery were planted. Dairo was learning to perceive the invisible: the subtle pulse of life, the undercurrent of emotion in a community, the silent stories whispered by places and people. While few could sense it, he began to hear what others could not—the precursors to the ghosts that would one day move through his music. These early encounters with sound would shape his understanding of music not just as art, but as a medium capable of summoning memory, emotion, and something far more mysterious than mere rhythm.

By the time he left adolescence, Dairo was no longer simply a boy playing instruments. He was a listener, a translator, and, unknowingly, a future conductor of forces that lay beneath the ordinary soundscape. He had begun to recognize that music could capture what was unseen, that rhythms could mirror memory, and that there existed a hidden world between notes, waiting for the right hands—and ears—to bring it to life. In the quiet moments before dawn, when Ibadan slept, Dairo could already sense the pulse of life that defied ordinary perception—a pulse that would later echo through the streets of Lagos, and perhaps, touch the ghosts themselves.

Lagos Awakens: Nightlife, Markets, and Musical Epiphanies

Israel Kolawole Dairo arrived in Lagos as a young man with curiosity sharper than ambition and a suitcase that carried little more than a guitar, notebooks, and the early instincts of a listener. The city hit him immediately—not with its traffic or formalities, but with its living rhythm. Markets hummed with energy long after sunset, vendors’ voices rose and fell in syncopated calls, and the distant creak of canoes along the lagoon punctuated the night. Lagos’ nightlife was improvisational and unstructured, a pulse invisible to most but impossible for Dairo to ignore.

He wandered through the districts, absorbing textures and patterns. The irregular cadence of footsteps on cobblestone, the spontaneous laughter of children darting between lantern-lit streets, and the melodic clash of calls from market traders—all became musical notes in his mind. Lagos presented itself as an open-air orchestra, every alley, every crowd, and every whisper of wind a potential instrument in an unfolding composition. He began sketching rhythms inspired directly by what he observed, translating the improvisational energy of the streets into layered percussion, guitar riffs, and melodic structures.

In the city’s heart, Dairo encountered the roots of what would become Juju music. Markets, street gatherings, and informal music sessions revealed the power of blending Yoruba percussion with Western instrumentation. Songs such as Ka Sora and Ise Oluwa began to emerge from these experiments, capturing Lagos’ multiplicity: the resilience of traders, the fleeting joys of street children, and the quiet dignity of women bearing unseen burdens. Each performance, whether in a crowded hall or under the open night sky, became a dialogue with the city itself, a reflection of both daily struggle and celebration.

Dairo’s performances were participatory by nature. Audiences did not simply watch; they became part of the music, clapping, singing, and swaying in sync with the rhythms. The city, too, seemed to have a voice: the creak of a boat, the call of a distant vendor, even the murmuring of wind through palm fronds blended seamlessly into the compositions. Through observation and improvisation, Dairo learned to shape music that mirrored the collective life of Lagos, bridging tradition and modernity, improvisation and structure, sound and experience.

Experimentation was central to his early musical development. Dairo adjusted tempo, layered percussion, and manipulated vocal inflection to explore how subtle changes could evoke laughter, tears, or reflective silence. He realized that music could act as a mirror for the city’s energy—capturing not just the audible, but the invisible pulse of human interaction, environment, and communal emotion. This sensitivity to rhythm and environment laid the groundwork for a new genre, one that would later define Lagos’ soundscape and the evolution of Juju music.

Even as Dairo honed his craft, he sensed something beyond the ordinary flow of life in Lagos. On certain nights, the city felt unusually responsive: notes lingered longer, rhythms aligned with ambient sounds, and fleeting patterns seemed to anticipate his musical choices. There was a sense that the city contained layers of memory and presence, imperceptible to most, yet tangible to someone willing to listen deeply. These subtle, almost imperceptible forces became part of the fabric of his early compositions, hinting at the ghostly undertones that would later define the immersive power of his music.

Through the nightlife, markets, and intimate performances of Lagos, Dairo discovered more than sound—he discovered a living entity in the city itself, one that breathed, pulsed, and whispered secrets. And in those quiet, restless hours, as rhythms intertwined with shadows and the night carried its myriad voices, there lingered a presence, unseen yet insistent. Something that seemed to await the right hands, the right ears, to translate its existence into melody. The ghosts of Lagos, though unspoken, were already listening.

The Orchestra of Ghosts: I.K. Dairo and the Blue Spots

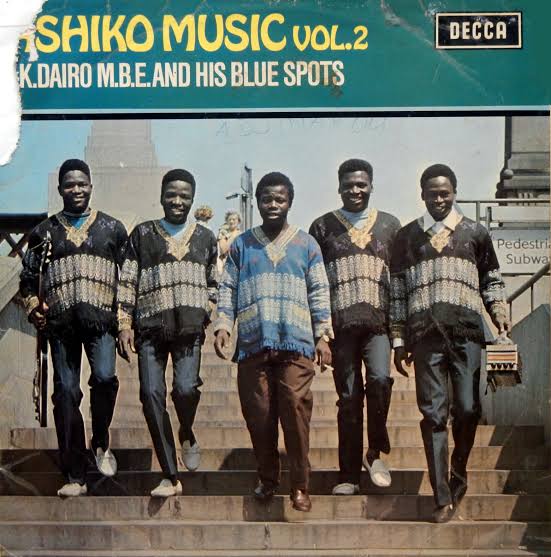

By the mid-1950s, Israel Kolawole Dairo had established himself as a formidable presence in Lagos’ musical scene, yet his true breakthrough came with the formation of his legendary ensemble: I.K. Dairo and the Blue Spots. More than a band, it was an extension of his consciousness—a collective capable of translating Lagos’ energy into music, shaping rhythm and melody as if in dialogue with the city itself. Every rehearsal, every performance became an experiment in precision, intuition, and something that defied explanation.

Dairo’s approach to collaboration was unlike that of conventional bandleaders. He did not merely direct; he conversed with his musicians through subtle gestures, eye contact, and calculated silences. Each instrument was treated as an independent voice, contributing to the polyphonic tapestry that defined Juju music. The talking drum, with its mimicry of human speech, spoke in tonal sentences; the guitar punctuated emotional crescendos; the shekere and other percussions wove complex rhythmic webs. To outsiders, it was music. To Dairo and his audience, it was a living organism, responsive to environment, emotion, and timing.

Audiences were often swept into a state of shared consciousness during performances. Clapping and dancing were expected, yet they became part of the architecture of the music itself, co-creating an ephemeral experience that existed only in that moment. People reported sensations that transcended ordinary listening—goosebumps, tears, laughter, and moments of contemplative silence. It was as if the music had an awareness, reaching beyond the conscious mind and tapping into memory, emotion, and, occasionally, something unseen.

The early Blue Spots repertoire fused Yoruba traditional music with Western harmonies and instrumentation, a pioneering step in modern Nigerian music. Songs were drawn from observation of city life: the markets, the streets, the labor and leisure of everyday Lagosians. But there were also compositions that seemed to arise spontaneously, melodies and rhythms that had not been pre-planned yet fit seamlessly within the ensemble. Dairo began to suspect that the city itself, or something within it, was influencing these moments—an invisible collaborator guiding the flow of creativity.

Touring and performances extended beyond Lagos. Radio broadcasts brought Dairo and the Blue Spots to a national audience, while international trips introduced Juju music to London, Paris, and other cultural hubs. Yet despite fame and acclaim, Dairo remained rooted in the rhythms of Lagos. His music was never abstract; it was a chronicle of lived experience, capturing stories of struggle, joy, love, and loss. Each drumbeat and guitar chord reflected the city’s heartbeat, the collective memory of its people, and the subtle energies of the environment.

And then, in the quiet moments between applause, Dairo would sense something extraordinary. Notes lingered longer than physics allowed, rhythms intertwined with ambient sounds in untraceable patterns, and melodies emerged that seemed to carry the weight of past conversations, lost voices, and unseen presences. He began to realize that there were ghosts embedded in the city, echoes of memory and history that responded to his music. Not supernatural in a simplistic sense, but subtle, persistent, and undeniable to anyone attuned to Lagos’ pulse.

In this way, Dairo did more than perform; he conducted an orchestra of both the living and the unseen. The Blue Spots were instruments in a larger symphony that included memory, place, and presence—forces that could not be named but could be felt. Through them, Lagos’ hidden layers came alive, giving audiences a glimpse of the city’s deeper life. It was in these performances that the first true convergence of music and ghostly resonance occurred, establishing a tradition that would define Juju music and secure Dairo’s place as a transformative figure in Nigerian musical history.

From Local Legend to National Icon

By the early 1960s, I.K. Dairo had become a son of Lagos whose voice echoed across Nigeria. His band, the Blue Spots, were more than musicians—they were cartographers of sound, mapping the city’s pulse into rhythms and melodies that spoke of markets, laughter, labor, and longing. Juju music, under Dairo’s hands, was no longer just entertainment; it was a living, breathing chronicle of a nation finding its own rhythm.

Songs like “Salome” danced like sunlight on the lagoon, playful yet deliberate, tracing the curves of Lagos’ streets and the gentle sway of its canoes. In contrast, “Ise Oluwa” flowed like sacred water through the city’s alleys, carrying spiritual weight and collective memory, a river in which listeners could immerse themselves, feeling both reflection and release. “Ko Soro F’oluwa”, meanwhile, struck like the echo of a drum at dawn, a reminder that music was also a messenger—insight wrapped in rhythm. Each song was a snapshot, a portrait painted in chords and percussion, capturing Lagos’ contradictions: joy and struggle, tradition and modernity, laughter and lingering shadows.

Albums like “Ashiko Music” and “Definitive Dairo” functioned as archives of the city’s invisible heartbeat. Each track acted as a window into Lagosian life, where voices from street corners and whispers from back alleys wove together in harmonic dialogue. Through these recordings, the Blue Spots did more than perform—they channeled the energy of a city, transmuting its restlessness, its celebrations, and its sorrow into melody. Even the quietest sections of a song seemed to hum with the memory of unseen lives, of footsteps long vanished and conversations that had shaped the rhythm of the streets.

As Dairo’s fame grew, so did the intensity of his connection to Lagos. National tours brought audiences across Nigeria into communion with his sound, yet it was the intimate knowledge of the city that gave his music its pulse. He listened to the cadence of market calls, the syncopated laughter of children, the rhythmic creak of boats on the lagoon—and translated these ephemeral movements into structured, yet fluid music. The city was his collaborator, and the Blue Spots were the instruments through which it spoke.

Even abroad, Dairo’s music carried the scent of Lagos’ nights. In London and Paris, audiences unfamiliar with Yoruba tonalities were swept into currents they could not name but could feel: the ebb and flow of rhythm as if the Atlantic itself had become a drum, carrying the pulse of Lagos across continents. His compositions were bridges, linking local memory with global resonance, traditional percussion with Western chords, and human experience with the intangible spirit of place.

And in the quiet spaces between notes, in the lingering decay of chords, Dairo felt it: a presence hovering at the edges of sound, subtle yet insistent. It was as if the city itself were leaning in, whispering through rhythms, offering guidance in melody. Ghosts of memory, fragments of past laughter, and echoes of lives long gone seemed to inhabit the pauses between beats, infusing his music with an almost sacred awareness. Listeners, unaware of this invisible layer, nonetheless felt it—a tremor beneath the song, a shadow that gave the music its depth and weight.

By weaving his songs and albums into these living rhythms, Dairo did more than achieve fame: he rendered Lagos audible in ways that were both immediate and eternal. He became a national icon not merely because of technical mastery, but because his music contained the essence of human experience, captured the city’s heartbeat, and allowed its unseen layers to resonate with those who listened closely.

In this phase of his life, Dairo’s rise was more than career—it was alchemy. Street sounds became symphonies; market chaos became orchestral phrasing; laughter, toil, and quiet reflection transformed into musical architecture. And in this architecture, somewhere in the shadows, the city’s ghosts began to hum alongside him, waiting to be fully recognized in the crescendos yet to come.

Echoes Through Time: Dairo’s Legacy in Modern Lagos

Decades after I.K. Dairo first strummed his guitar and coaxed the talking drum into conversation, his music still breathes through Lagos. Modern Afrobeats, Fuji, and contemporary Juju artists, including his son Paul Babatunde Dairo aka Paul Play carry traces of his rhythms, layering them into new sounds that speak to today’s generation while keeping the heartbeat of the city alive.

Even in nightclubs or home stereos, the cadence of Dairo’s compositions resonates—a subtle reminder that the past never truly leaves.

His albums function as living archives. They are more than recordings; they are sonic maps of a Lagos that once was and, through memory and influence, continues to shape the city’s identity. Young musicians study his arrangements, noting how he layered percussion, used harmonic tension, and wove storytelling into every measure. Each note is a lesson in connecting the tangible with the intangible, the immediate with the timeless.

Beyond technical influence, Dairo’s work preserved emotional landscapes. His songs captured both communal joy and private sorrow, translating the rhythms of markets, the cadence of street life, and the whispers of ancestors into melodies that remain familiar to Lagosians today. Listeners experience these tracks not just as entertainment, but as empathy made audible—a bridge between human experience and collective memory.

Even more remarkably, certain elements of his music hint at the invisible orchestra he once conducted. Musicians and audience members alike have reported moments when rhythms seem to anticipate gestures, or melodies resolve in ways unplanned yet perfect. There is a subtle, almost mystical quality to these experiences—the sense that the city itself, along with its history and unseen presences, continues to hum alongside his compositions. Dairo’s music thus functions as a conduit, linking the living, the remembered, and the spectral.

Contemporary Lagos thrives on reinvention, yet Dairo’s influence persists as a foundational pulse. Sampling of his tracks in modern productions ensures that his rhythms reach new audiences, while live performances by younger Juju bands echo his structural and harmonic innovations. His approach—fusing tradition with modernity, human emotion with musical craft—remains a template for balancing authenticity with evolution.

For those attuned to his subtler layers, there is something more: the ghostly resonance that has threaded through his music since the early days. In quiet moments between beats, in the lingering decay of chords, listeners can sense a presence that seems alive, attentive, and patient. It is the city itself, or perhaps the memory of its inhabitants, past and present, playing alongside Dairo’s orchestra of ghosts. This spectral accompaniment is never explicit, yet it imbues the music with an emotional depth that cannot be taught or replicated.

Through all this, Dairo’s legacy is not just historical—it is active, evolving, and omnipresent. His compositions continue to guide musicians, influence audiences, and shape the identity of Lagos itself. Each time a guitarist strikes a familiar riff or a drummer echoes his syncopations, the city’s pulse aligns once more with the rhythms he first drew from its streets. In essence, Dairo’s music remains a living conversation between generations, between the tangible and the invisible, between the human and the ghostly.

Ultimately, the echo of I.K. Dairo’s music in modern Lagos is proof that his work was never just his own. The rhythms, stories, and harmonies he shaped belong simultaneously to the city, its people, and the layers of memory and spirit that move unseen among them. In every venue, studio, or market corner where his influence persists, the orchestra he conducted still plays, reminding listeners that Lagos’ soul—and its ghosts—remain audible to those willing to listen.

Summation: The Last Note

The city slept, but its silence was never empty. Somewhere between the flickering streetlights and the whispering alleyways, a faint rhythm lingered, a trace of lives that had come and gone. I.K. Dairo, who had walked these streets and coaxed their invisible currents into song, had himself departed—his life ending quietly in 1996 after a long illness, a peaceful exit that mirrored the gentle ebb of his music. Yet even in death, the presence he had always sensed in Lagos seemed to gather around him, as if the city itself had waited for his final note.

In the empty halls and quiet corners where his compositions once played, one could almost feel him still conducting, eyes closed, guiding the Blue Spots, and listening to the ghostly echoes of the city he had long translated into rhythm. The melodies did not die with him; they persisted in the hum of the harbor, the creak of shutters, the sway of palm trees, carrying memories, histories, and the faint laughter of streets long past.

His death did not silence the orchestra—it transformed it. The ghosts he had long intuited, the unseen presences threading through his music, now seemed freer to speak, lingering in pauses between chords, shaping harmonies in ways no living hand could. It was as though Lagos night itself had absorbed him, allowing him to continue conducting an orchestra that existed between the living and the unseen.

As the first light of dawn broke over the city, Lagos awoke unaware of the symphony that had passed through it in the night, yet subtly altered by it. Those who had truly listened—the ones attuned to the city’s heartbeat—felt the resonance linger, an echo of a man who had understood that music could be both human and spectral, mortal and eternal. I.K. Dairo had died, but the orchestra of ghosts he conducted, and the pulse of the city he had heard, would never cease.