There’s a particular kind of magic that happens when people see themselves reflected on screen for the first time, not through the lens of foreign filmmakers, not filtered through Western perspectives, but raw, authentic, unmistakably theirs.

In Nigeria, during the 1990s and 2000s, this magic exploded across television screens in living rooms across Nigeria, creating something nobody expected: a film industry that would become the world’s second-largest by volume and, more importantly, the mirror through which Nigerians understood themselves.

They were moral lessons, cautionary tales, celebrations, and warnings. They were the stories grandmothers told, repackaged for the video age. They were uniquely, unapologetically Nigerian, and they changed everything.

READ THIS: Netflix Eyes Champions League Rights in Bold Move to Attract New Users

1. Living in Bondage (1992)

Every revolution has a flashpoint, and for Nollywood, it was a two-part thriller released when nobody believed Nigerians would pay to watch Nigerian stories. Directed by Chris Obi Rapu, written by Kenneth Nnebue and Okechukwu Ogunjiofor, the film tells the story of Andy Okeke, a struggling young man who joins a secret occult society to gain wealth, sacrificing his wife in the process.

What follows is his descent into madness, haunted by her ghost, unable to enjoy the riches he gained through her blood. The film tapped into something profound in Nigerian consciousness: the tension between traditional spiritual beliefs and modern materialism, the costs of ambition, the reality of occult practices in contemporary Nigeria, and the consequences of moral compromise.

Andy’s story was cautionary but recognisable. Everyone knew someone like Andy, ambitious, impatient, and willing to cut corners for success. The film’s spiritual elements weren’t fantasy; they reflected genuine beliefs held across Nigerian society, regardless of religion or education.

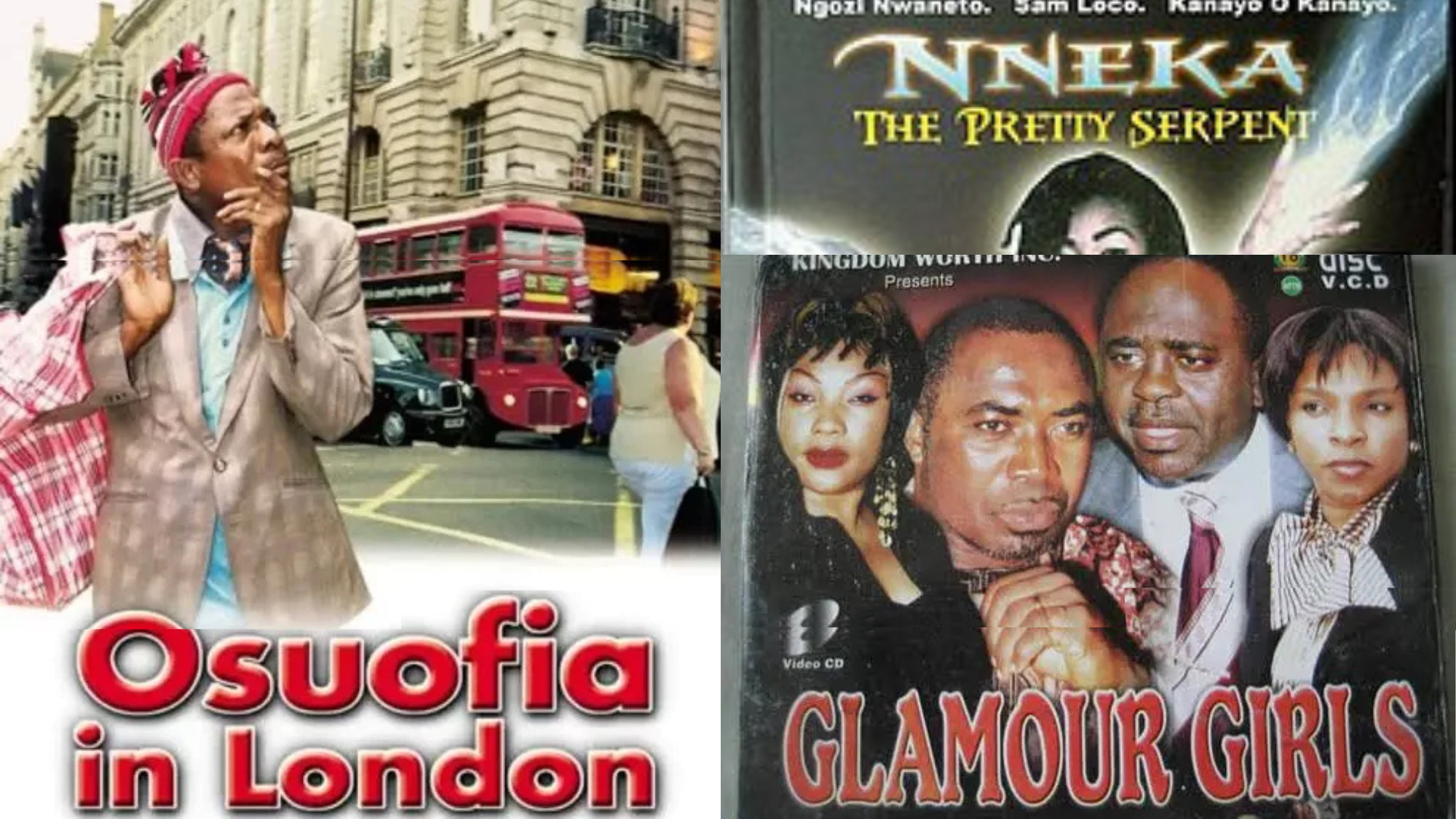

2. Glamour Girls (1994)

Two years after Living in Bondage, Glamour Girls held up another mirror to Nigerian society, this one reflecting the lives of young women navigating Lagos’s treacherous intersection of beauty, ambition, poverty, and exploitation.

Directed by Chika Onukwufor, Glamour Girls followed a group of beautiful young women drawn into high-class prostitution, sugar daddy relationships, and the seductive but dangerous world of transactional relationships with wealthy men.

The film didn’t simply moralise; it explored complex motivations, systemic pressures, and the limited options facing beautiful young women from poor backgrounds in a society that commodified beauty while offering few legitimate paths to prosperity.

Glamour Girls sparked intense conversations in Nigerian homes, churches, and social circles.

Parents used it as a teaching tool, warning daughters about the dangers of materialism and quick money. Young women saw themselves and their struggles reflected, the pressure to help struggling families, the temptation of luxury, the predatory older men, and the competitive friendships that could turn toxic.

The film didn’t shy away from uncomfortable truths. It showed how poverty pushed women toward exploitation. It depicted the casual cruelty of wealthy men. It explored how desperation made dangerous choices seem reasonable.

And crucially, it showed consequences, how this lifestyle destroyed women, how temporary pleasures led to lasting pain. But the film also captured something else: the genuine friendships between women navigating impossible situations together, the moments of laughter and solidarity, the dreams that motivated risky choices.

The “glamour girls” weren’t simply victims or villains; they were complex human beings making the best decisions they could with limited options.

3. Nneka the Pretty Serpent (1994)

Nigerian folklore and mythology are rich with stories of shape-shifters, water spirits, forest deities, and mystical beings. Nneka the Pretty Serpent brought these ancient stories into modern Lagos, creating a film that was simultaneously horror, fantasy, romance, and a cautionary tale.

The story followed Nneka, a beautiful woman who was actually a snake deity sent to the human world on a mission. She fell in love with a human man, creating complications as her serpent nature conflicted with human emotions.

The film explored themes of identity, belonging, forbidden love, and the tensions between traditional spirituality and modern life.

Nneka the Pretty Serpent pushed Nollywood’s technical boundaries. The transformation sequences, crude by Hollywood standards but impressive for low-budget Nigerian video, captured imaginations. Audiences suspended disbelief not because the effects were flawless but because the story’s emotional and spiritual core felt true.

The film demonstrated that Nollywood could do more than contemporary dramas. It could explore fantasy, horror, and mythology, genres deeply rooted in Nigerian storytelling traditions. This opened creative possibilities, encouraging filmmakers to adapt folklore, legends, and spiritual stories that had been told orally for generations.

4. Rattlesnake (1995)

Before Rattlesnake, Nollywood hadn’t really tackled action genres. The film changed that, telling the story of Ahanna, a young man who becomes a notorious armed robber, terrorising Lagos before his eventual downfall.

What made Rattlesnake significant for its exploration of criminality’s roots. The film examined poverty, lack of opportunity, peer pressure, and systemic failures that pushed young men toward crime. Ahanna was a product of circumstances, making choices that seemed logical given his environment.

Rattlesnake introduced Nigerian audiences to the complicated anti-hero. Ahanna was criminal, violent, destructive, but also charismatic, loyal to his crew, and ultimately tragic.

Audiences sympathised even while condemning his actions, recognising how easily circumstances could create criminals from ordinary people.This moral complexity marked Nollywood’s maturation. Early films often featured clear villains and heroes.

Rattlesnake acknowledged that reality was messier, that good people made bad choices, that society bore responsibility for individual failures, that redemption was possible even for the fallen.