There are moments in a performer’s life when acting ceases to be imitation and becomes revelation.

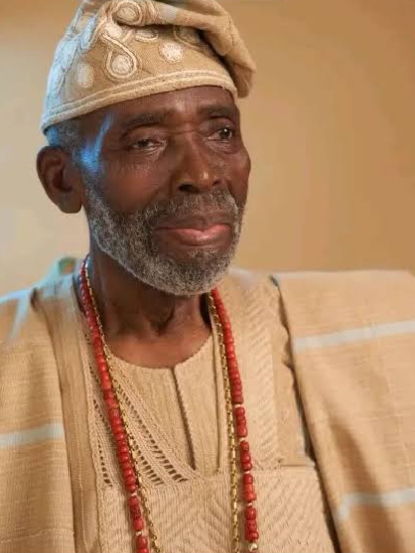

Olu Jacobs, then seventy-five, sat alone between takes, his hands clasped, eyes fixed on something only he could see. Crew members had learned to leave him to his silences. Joke Silva, his wife and scene partner, understood that those silences were preparation. Jacobs did not simply “get into character.” He allowed the character to inhabit him.

When the director called “action,” Jacobs rose with the grace of a monarch and the vulnerability of an old man who had seen too much.

In one brief, unscripted moment, he paused before speaking, his eyes moist, the camera lingering long enough to catch the tremor in his lips. It was supposed to be a small domestic scene; it became something else entirely. Everyone on set felt the shift.

Later, when the scene played in theaters, it landed with quiet force. Viewers who had followed Jacobs since the 1970s recognized the familiar gravitas—what critics once called his “regal melancholy.” It was as though decades of stage discipline, television realism, and personal history had collapsed into a single breath.

That brief hesitation before his line recalled the exhaustion of kings, fathers, and soldiers he had portrayed across continents. It was the moment that confirmed, once more, why he was often called Nigeria’s Laurence Olivier.

But what few realized then was that the same qualities that elevated him—his total surrender to craft, his relentless interior excavation—were also eroding him. Each performance drew from deeper memory, and memory itself was beginning to slip away.

The British Schooling of a Nigerian Soul

Long before Nollywood existed, a young Oludotun Jacobs left the port city of Abeokuta for London, clutching a letter of admission to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. The year was 1964, and Nigeria was only four years independent. London was cold, gray, and hierarchically polite; the theater world even more so. Yet inside RADA’s narrow rehearsal rooms, Jacobs felt an awakening. He learned the sacred rhythm of the stage—projection, diction, pause, presence. He studied Chekhov, Shakespeare, and Ibsen under instructors who treated the stage as altar.

He watched Laurence Olivier perform Othello on film and was stunned by the precision—the way Olivier used restraint to intensify emotion. Jacobs began to dissect that technique, not to imitate it but to understand how voice could command silence. The British system prized control; Jacobs’s Yoruba upbringing prized empathy. Between those poles he began forging his signature: the intellectual authority of classical acting tempered by the warmth of oral tradition.

Through the 1970s, he performed in British television dramas—The Goodies, The Professionals, Barlow at Large—and in stage productions across the U.K. He was often cast as “the African officer” or “the diplomat,” roles shaped by colonial imagination. Yet even within those constraints he radiated presence. Colleagues noted how he filled a room without movement, how stillness became his power. That quiet magnetism would become the hallmark of his Nigerian career.

Still, London could only teach him form, not belonging. The applause was polite, the opportunities limited. After more than a decade abroad, he began to feel what he later called “a hunger for home.” He realized that his voice—rich, deliberate, unmistakably African—belonged to a continent still searching for its cinematic language.

Crossing the Atlantic of Identity

When Jacobs returned to Nigeria in the late 1970s, the nation was electric with cultural experimentation. Television dramas like The Village Headmaster and The New Masquerade had made the small screen a national ritual. Theatre companies were adapting folk tales for modern audiences. It was a perfect moment for a man trained in Britain but rooted in Yoruba storytelling.

He joined productions that would later define Nigerian television: Mirror in the Sun, Checkmate, Play of the Week. His diction distinguished him, but it was his emotional control that mesmerized audiences. Where others shouted, he whispered; where others gestured wildly, he stood still. Directors began to reserve for him roles of power—chiefs, judges, patriarchs—figures whose authority derived less from words than from presence.

His international experience also attracted film producers. In 1980, he appeared alongside Christopher Walken in John Irvin’s The Dogs of War. The film was a British-American production about mercenaries in Africa, and Jacobs played President Kimba, a ruthless yet tragic leader. For many Nigerians watching later, it was a revelation: one of their own commanding the screen with Hollywood stars. The camera adored his composure; he made tyranny seem weary rather than loud. That performance would become, in retrospect, his defining “scene”—the first time the world saw the full measure of his artistry.

Yet fame abroad came with irony. While the West praised his authenticity, he longed to tell stories that spoke to his people’s realities. Returning fully to Nigeria, he carried with him not only training but also a mission—to prove that African acting could be classical without losing its soul.

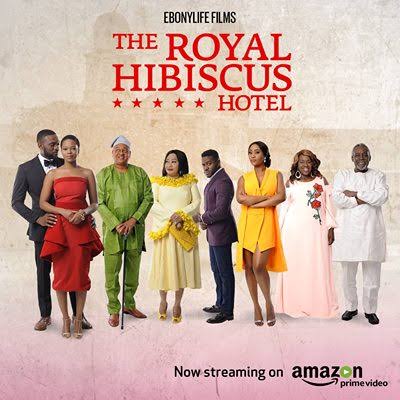

The Scene That Reportedly Broke Him

It reportedly happened on a quiet afternoon in Lagos, during the filming of The Royal Hibiscus Hotel — a romantic drama that, on paper, seemed far too light for the kind of gravitas Olu Jacobs was known for. But in one pivotal scene, as Richard, the aging father struggling to hold his family together, Jacobs turned what should have been a routine emotional exchange into something that stopped time.

The camera found his face — tired, kind, heavy with unspoken years — and in a single look, he delivered a masterclass in restraint. No tears. No grand gestures. Just silence layered with a lifetime of knowing.

Those who had worked with him recognized what they were witnessing. Jacobs had always said that great acting was not about pretending; it was about understanding what a human being would never say out loud. In that scene, the camera didn’t just record a performance — it captured the body of a man who had spent decades turning words into wisdom, now stripped down to the bare truth of feeling.

What made the moment even more haunting was what followed off-screen. Those close to Jacobs began to notice his memory faltering not long after filming wrapped. Lines he once recalled effortlessly began to fade. His wife, Joke Silva, would later speak softly about “the gradual retreat of the mind.” Watching that scene now feels like watching a man unknowingly perform his own goodbye — an artist confronting his fading faculties through the only language he had ever mastered: stillness.

It broke him not in scandal or defeat, but in surrender. He had poured everything left of himself into that brief on-screen moment, as though he sensed it would be his last lucid act of creation.

According to reports, when the cameras stopped rolling, everyone clapped. Jacobs smiled, but his eyes were elsewhere — somewhere between the man he had been and the memory already slipping away.

How the Scene in The Royal Hibiscus Hotel Made Him Nigeria’s Laurence Olivier

It wasn’t the grandest scene of his career, nor the most talked-about, but it was the one that reportedly defined him. In The Royal Hibiscus Hotel, Olu Jacobs’s Richard was a man standing at the crossroads of memory and regret — a father whose silence said more than dialogue ever could. In that silence lay the essence of what English Actor and Director Laurence Olivier embodied on the global stage: command through calm, magnetism through minimalism.

Jacobs didn’t dominate the frame by force; he conquered it by absence, by restraint. His stillness drew the audience in like a gravitational pull — you couldn’t look away, because you felt something eternal being said without sound.

The comparison to Olivier came naturally to filmmakers who understood what Jacobs had achieved. Olivier had built a legacy on making Shakespeare human, not mythical. Jacobs, in that one sequence, did the same for Nollywood’s emotional vocabulary. He stripped performance of its excess, proved that vulnerability could exist without weakness — that a Nigerian man on screen could cry inwardly and still stand tall.

In a cinematic culture often driven by visible emotion, Jacobs’s Richard reminded audiences that dignity could coexist with despair, and that truth doesn’t always announce itself — sometimes it just lingers in the eyes.

What made the scene unforgettable wasn’t technique alone; it was what he carried into it. Decades of stage discipline from his training in London’s Royal Academy of Dramatic Art had sculpted his instincts. He understood pacing, breath, and silence in ways few actors around him could match.

He didn’t merely act as Richard — he became him, embodying the generational ache of fathers who love imperfectly but deeply. The performance was so controlled it felt effortless, but anyone who knew Jacobs’s craft recognized the invisible architecture beneath it: a man drawing on every layer of experience, loss, and learned restraint.

When the scene ended, the set fell quiet. The director, Ishaya Bako, reportedly didn’t yell “Cut” immediately. Crew members exchanged looks — the kind people share when they realize they’ve witnessed something more than a take.

In that pause, Jacobs had joined the lineage of global performers who transcend acting — those who channel life itself into art. That was the moment Nigeria saw its own Laurence Olivier — not because he mirrored the British icon, but because he proved that Nigerian cinema could produce its own version of timeless grace, born from cultural truth and human stillness.

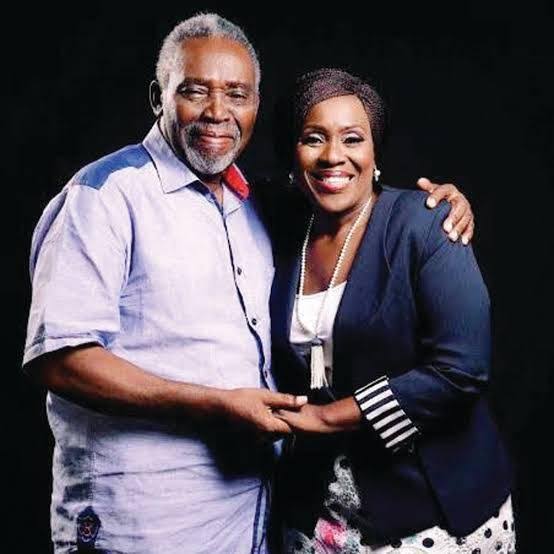

Joke Silva: The Witness of His Second Act

Every titan needs a counterpart who understands the silence between triumphs. Joke Silva was that counterpart. When they met in the early 1980s during a stage production at the National Theatre in Lagos, she was captivated not by his fame but by his discipline. Over four decades of marriage, they built what many consider Nigeria’s first acting dynasty—partners on stage and off, equals in intellect and spirit.

Together they co-founded Lufodo Productions, a company that trained young actors in professional technique. They taught workshops on voice, movement, and ethics—insisting that performance without integrity was empty. To students, they were affectionately “Uncle Olu” and “Aunty Joke.” To each other, they were mirror and anchor.

By the mid-2010s, Silva began to notice subtle changes. Lines forgotten, rehearsals shortened. Yet when the cameras rolled, he transformed again—the muscle memory of decades overriding frailty. During movie shoots, observers said his timing and humor were intact, but between takes he often drifted into reverie. Silva shielded him gently, ensuring no one mistook fragility for weakness.

Their public appearances in later years—hand in hand at award ceremonies, her steadying him as flashbulbs popped—became emblems of endurance. When she finally confirmed his diagnosis of dementia, Nigerians responded not with pity but reverence. They saw a couple whose love was performance in its purest form: devotion without audience.

Fading Spotlight

In the quiet years that followed, Jacobs receded from the stage he had built. Photographs showed him smiling faintly, the leonine features softened but still dignified. The industry that once depended on his authority now spoke of him in the past tense, though he was still among them. For the younger actors—Ramsey Nouah, Richard Mofe-Damijo, and others—his method had become gospel.

Dementia is cruel to performers; it erases the very instrument of their craft—memory. Yet even as recollection faded, fragments of dialogue returned unbidden. During visits, friends recalled him reciting Shakespearean lines with startling clarity before lapsing into silence. It was as though the roles had outlived the man, echoing in the recesses where self once resided.

Observers drew parallels to Olivier’s own decline. Both men, icons of their nations’ theaters, faced the indignity of forgetfulness after lives devoted to remembering. But in Jacobs’s case, the tragedy carried an African poignancy: a griot who could no longer recall the stories he had once embodied.

Still, legacy works differently in oral cultures. In Nigeria, memory is communal. While his mind dimmed, the nation’s collective memory brightened. Television reruns, film retrospectives, and tributes on social media kept his voice alive. In losing his memory, he became everyone else’s.

Legacy of the King Who Remembered Everyone but Himself

Today, Olu Jacobs stands not merely as an actor but as architecture—a pillar connecting colonial-era theatre to global Nollywood. His career charted the evolution of African performance from imitation to originality. Every controlled breath, every regal pause, every measured inflection became a grammar through which Nigerian actors learned to speak complexity.

The comparison to Laurence Olivier now feels less about likeness and more about lineage. Both men proved that acting could dignify a nation’s imagination. Olivier gave Britain its cinematic Shakespeare; Jacobs gave Nigeria its moral center on screen. Where Olivier’s kings spoke of empire, Jacobs’s chiefs spoke of community. His art translated power into empathy.

In classrooms from Lagos to Accra, young actors still study his films, noting how he turned restraint into electricity. Critics describe his career as “the bridge between theatre and film, between Europe and Africa, between authority and tenderness.” That bridge remains intact, even as its builder withdraws into the shadows of memory.

The scene that made Olu Jacobs Nigeria’s Laurence Olivier—the moment he fused discipline and depth, intellect and emotion—also marked the beginning of his undoing. But perhaps that is the artist’s eternal paradox: to give everything until there is nothing left to give. He once said acting was “the privilege of feeling for many.” He felt enough for generations. And though his mind may wander, his work remains—steady, sovereign, unforgettable.

Final Act: The Silence That Speaks

Olu Jacobs showed that mastery is a double-edged gift. It elevates the artist above ordinary perception, yet exposes the fragility beneath. In the years after the performances that made him immortal, when memory faltered and words abandoned him, he remained a presence — quiet, dignified, and unshakably human. His genius did not vanish; it lingered in gestures, in silences, in the subtle orchestration of emotion that only he could command.

Every frame he touched, every scene he inhabited, carries a weight that defies time. It is not the memory of the actor alone that lingers, but the imprint of his discipline, his insight into human frailty, and the way he made ordinary gestures speak volumes. Jacobs taught that cinema could be a mirror of the soul, and that the quietest moments often resonate the longest.

Perhaps the greatest lesson of Jacobs’s life is this: brilliance carries cost, and yet its resonance transcends mortality. Even as the man receded into quiet, the work remains alive, shaping the eyes, minds, and hearts of all who encounter it. In that silence, there is both grief and awe — a haunting proof that true artistry, once fully realized, is eternal.